420 origins traced to San Rafael's 'Waldos'

All five members of the Waldos as adults. (Waldos, LLC)

OAKLAND, Calif. - Marijuana culture's high holiday, 420, falls on Saturday this year, an occasion celebrated by pot enthusiasts around the globe who gather under the haze of cannabis smoke by sharing joints in camaraderie.

But why is April 20 the day to light up? The origins stem from a group of five Marin County men, now in their 60s, who coined the slang term in 1971 while students at San Rafael High School. The group called themselves "the Waldos," a term first used by comedian Buddy Hackett to describe odd people.

The clique consisted of David Reddix, Steve Capper, Larry Schwartz, Jeff Noel, and Mark Gravich, who routinely gathered at a specific spot on campus.

"We used to meet on this wall in the middle of school. And that's how we got our name," Reddix said. The then-teenagers were jokesters or "social satirists" whose only agenda was to bring laughter to those around them. They also just happened to indulge in marijuana.

Early days of 420

"Sure, we smoked a lot of weed, but it wasn't so much about pot. It was more about just the humor between us," Capper said.

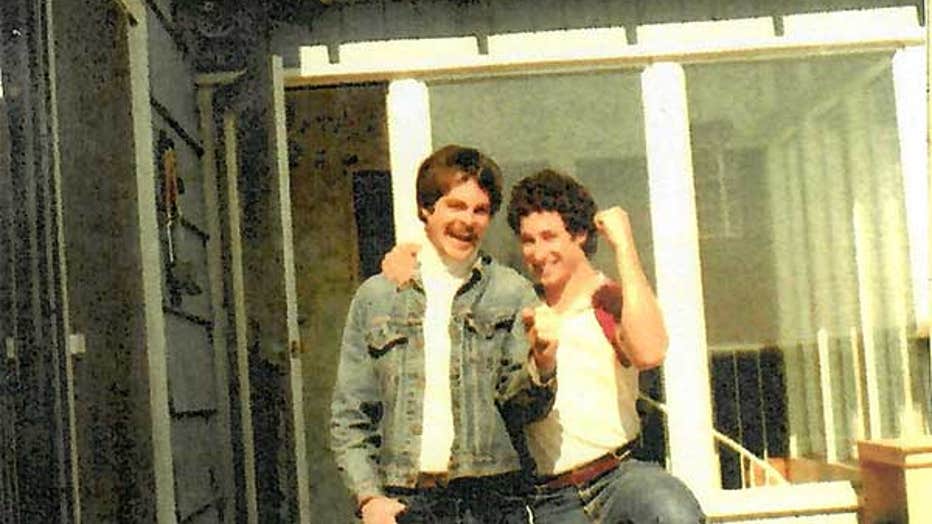

Waldos members David Reddix and Mark Gravich pictured in this undated photo. (Waldos, LLC)

"The weed just enhanced our humor," said Reddix, a filmmaker and retired cameraman and field producer for CNN in San Francisco.

The "420" reference first emerged just ahead of a "Waldo Safari," described by Reddix and Capper as field trips where the group would explore the Bay Area and beyond. One of these excursions involved a search for a cannabis patch. Capper explained that a friend's brother, a member of the US Coast Guard stationed at Point Reyes, was growing cannabis there.

"For some reason, they got paranoid that their commanding officer was going to bust them. So they decided to abandon the patch," Capper recalled.

Capper said his friend's brother drew a map and gave the teens the go-ahead to harvest the potent crop.

"We got very excited. Free weed. Back in the day. It was a no-brainer," he said.

The Waldos eagerly ventured on their Waldo Safari to find the illicit grove.

"We decided to meet after school. There's a statue of the chemist Louis Pasteur, who invented pasteurization, and we decided to meet at the school at the statue at 4:20 p.m.," Capper explained. He said the group chose that exact time for various reasons; some of the Waldos had football practice or study hall earlier in the day, so priorities came first, and then the fun followed.

Reddix remembered, "We would get high and then jump into Steve's '66 Impala with the killer eight-track stereo and drive out to Point Reyes looking for this patch."

After the first failed mission, the Waldos decided to continue their quest for the elusive marijuana crop, using the term "420 Louis" as a reminder for the afterschool meet-up.

Though they never found the plants, their private lexicon — "420 Louie" and later just "420"— stuck.

Use the code

"We had a term for marijuana that our parents wouldn't know, or the cops wouldn't know. The teachers wouldn't know," said Reddix. "So, we used it as a secret code."

One of the most widespread falsities about the origins of 420 was that it was a police code for being caught with marijuana, which the group flatly refutes.

The Waldos used the low-key code exclusively to signal meeting up after school to get high. The group had to keep their activities discreet as marijuana use at that time was illegal and carried stiff penalties.

Under the 1970 Controlled Substances Act, marijuana was classified as a Schedule I substance, where it has remained ever since, indicating a high potential for abuse, according to the Drug Enforcement Administration.

Waldos member Larry Schwartz seen pictured in this undated photo.

"When we were driving around smoking weed, looking for weed, buying weed. People forget how horribly illegal it was. You could be seen in your car (smoking marijuana) and you go to prison for years," said Capper. "We were constantly looking over our shoulder, constant paranoia."

There were no dispensaries back then, as widely seen across California now, after the state legalized recreational marijuana use in 2016. In those days, the Waldos got their cannabis from acquaintances or dealers.

"You never knew what kind of weed or what the THC percentage was. So every single time you smoked, it was Russian roulette," joked Capper, who said that back then, purchasing weed was a gamble. "Sometimes, it's pretty astonishing."

420 goes mainstream

The 420 code was exclusively used among the group, but the slang trickled outside the Waldos through their connections and ties to the rock band Grateful Dead and the Deadheads community, who adopted the code.

"Backstage where I was getting high with guys like David Crosby, Phil Lesh, Terry Haggerty, it started filtering through the Deadheads and the roadies," recalled Reddix, whose brother was good friends with Lesh, the Grateful Dead bass player. "Then it became kind of viral before the internet."

The term further blossomed into popularity.

In the early 1990s, Steve Bloom, a reporter for the cannabis-focused High Times magazine, was at a Grateful Dead show in Oakland when he was handed a flier urging people to "meet at 4:20 on 4/20 for 420-ing in Marin County at the Bolinas Ridge sunset spot on Mt. Tamalpais."

Reddix said that the High Times published this information in the magazine and the group has documentation of that along with postmarked letters exchanged between the Waldos discussing 420 in the 1970s. The Waldos said there is no denying they are the creators of the phrase.

San Francisco to host first-ever Weed Week

Cannabis fans will have an opportunity to celebrate in the city of San Francisco after all. The city announced that its annual 420 event in Golden Gate Park would be canceled this year due to budget cuts, but the cannabis community had another idea in mind.

Today, the catchphrase permeates through mainstream culture, so much so that April 20 is widely known as a day to indulge in all things cannabis.

Many states across the U.S. have relaxed restrictions and increased tolerance for the plant’s use. The Waldos find the evolution of marijuana acceptance fascinating.

"When I drive in the East Bay, I see a billboard, 'Delivery, marijuana to your door.' It's mind-boggling to us people of our generation," Capper said. "It's mind-boggling that somebody can deliver what you need to your door."

Reddix expressed that he never imagined a time when recreational marijuana use would be legalized.

"We never thought that it would be legal, back when we were smoking it in high school, it was like an impossibility," he said.

Added Capper, "We were the Forest Gump of weed."

Still celebrating

Now, when they catch the spirit of 420 on April 20, they will reminisce on the changes they have witnessed — some of which they helped bring about — from its prohibition to its legalization.

The gang still indulges in cannabis, though they have different preferences for marijuana products, and they still celebrate the high holiday together.

Reddix said that their modern tradition is to meet at the Lagunitas Brewing Company in Petaluma and grab "The Waldos Special Ale," crafted by the brewery in honor of the group. The Waldos also sell themed apparel and rolling paper on their website.

Reddix recalled trying San Francisco's Hippie Hill over a decade ago for 420, describing it as a "cacophony of craziness" with thick clouds of smoke hanging over Golden Gate Park.

Despite San Francisco canceling this year's Hippie Hill bash, Reddix and Capper said there is still cause for celebration on 420, just elsewhere.

"That's not the end of 420. People are still going to celebrate," Capper said. "They're going to go to lounges, they're going to go to clubs, they can go to an art gallery (and) if you're real hungry, you can go to a donut shop."

While the Waldos have gained notoriety for being the true originators of the 420 slogans, they return to their private lives once the high holiday passes.

"Every year it's like putting up decorations for Christmas. And then when it's over, we can take a deep breath and say, 'Thank goodness, God, it's over,'" Reddix said playfully.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.