Bay Area mom, NYT bestselling author shares her experiences amid rise in racism toward Asian-Americans

RICHMOND, Calif. - An award-winning Bay Area author is advancing the conversation about racism and offering opportunity for dialogue, following incidents during which she was targeted for the color of her skin.

New York Times bestselling author and Bay Area resident Kelly Yang (Kelly Yang)

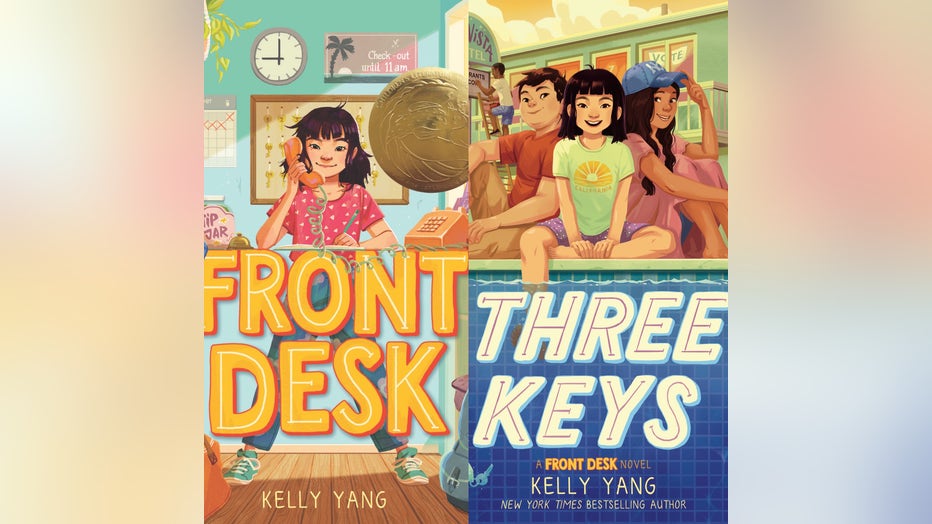

East Bay resident Kelly Yang is a young adult novelist and author of New York Times best selling middle-grade novel, "Front Desk" with the book’s sequel "Three Keys" set to come out in September.

When the pandemic hit and shelter-in-place orders effectively ended in-class learning in schools, Yang decided to launch a virtual writing class for teenagers on Instagram Live.

“I wanted to do something to help the community. I had spent a lot of time teaching before I became a novelist,” Yang told KTVU. “A lot of people were feeling they wanted an outlet, but didn't know how to access it. I really wanted to give kids a way to learn from a professional author for free during this really scary time.”

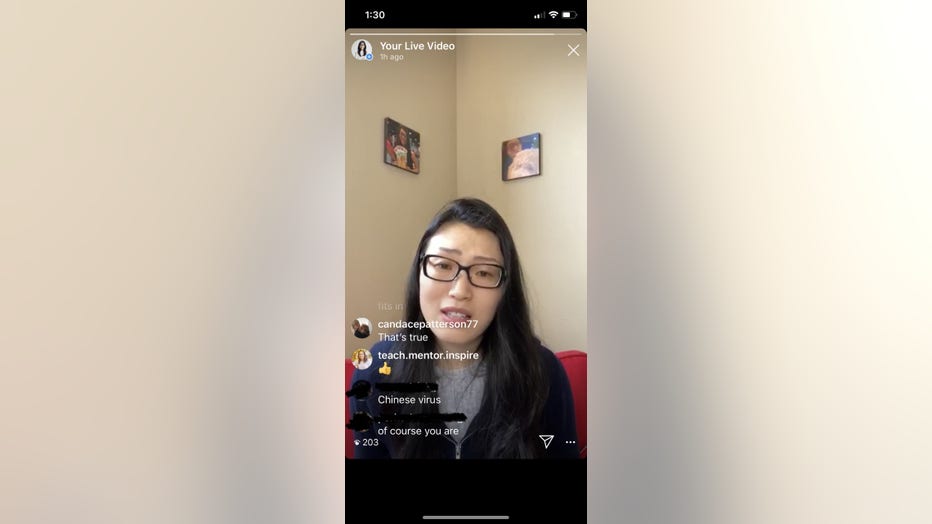

It was during one of these classes when a teenage student typed out “Chinese virus” and then “of course you are” in the comment section. He wrote it a couple of times during the half-hour class, and Yang said honestly, it took a minute for her to realize the words were directed at her. It was a jarring experience.

(Kelly Yang)

“For me as the instructor, I was freaking out. I wasn't sure what to do. My first instinct as a teacher was, I can't let this derail my class,” she said.

SIGN UP FOR THE KTVU NEWSLETTER

So Yang resolved to get through the class, doing her best to ignore the comments. But afterward, she knew this incident was not something that could or should be ignored, especially after the comments ended up getting circulated on social media.

“Several people had screenshot it,” Yang explained. “I realized I couldn't just be silent on this… and so I decide to write look this happened. This is not okay.”

She described the incident as devastating and hurtful and encouraged families to use it as an opportunity to spark conversation with their own kids.

“I spent most of today crying and even though it happened to me, it’s a reminder to all of the racism happening against Asian Americans, particularly students and kids, all the microaggressions & aggression that we’ve had to stomach for years,” she wrote on Twitter. “So pls do me a favor, use what happened to me to check in w ur kids and have a conversation w them. Let’s bond and heal, together.”

Yang followed up with a video message posted to social media that started with the words, “There’s no such thing as ‘casual racism.’ It’s just racism.”

The writer stressed the importance of recognizing when such incidents occur and using them as springboards to get educated and to learn.

“It’s racist to call a virus a Chinese virus,” she said on Instagram. “And so when people say Chinese virus, and I know that our president has called it that, it makes it almost okay for everybody else to tap into whatever reserve of racism they already had to begin with,” she told her audience.

That video received almost 1,700 views and comments from many people who thanked the author for using the situation as a teaching moment.

Yang said she later received an apology from the teen who made the comments. He sent her a message saying he thought he was being funny and just wanted to make his friends laugh, though he now realized that he was being disrespectful and racist. She responded by thanking him for the apology and recognized it as an opportunity for the teen to learn and grow.

About a month after that incident, Yang encountered another act of racism in a park in Richmond. She was on a walk with her kids and dog. Yang said she did not realize dogs had to be on leash and didn't see the sign that state that, and suddenly a woman charged toward her and asked, “Can you read, you Oriental?” Yang immediately leashed her dog, but the woman kept moving toward her, even as she asked the woman to back off.

“Then her husband starts coming over —the two of them are storming over without a mask—and says go back to where you came from,” Yang wrote on Twitter.

She said when the couple kept coming toward her and her kids, that’s when she took out her camera and started recording, which finally got the man and woman to turn around and walk away.

Yang was left shaken, and she said her kids were left thoroughly confused. They asked what the couple meant by going "back where you came from?" Her 10-year-old son asked whether it meant they should leave the park and go back to their house.

Upon returning to their car, Yang felt the need to immediately explain what had just happened and what the couple’s hurtful words meant, noting that the word Oriental was one her kids had never heard. “Then they’re eyes welled up,” the mother of three explained.

Yang said her eldest son was back at home and when they told the 13-year-old and her husband about the encounter, the teenager had a different reaction. “My oldest son was really upset but was really embarrassed, and he didn’ want me to put it up on Twitter,” the mom explained. “He was like, 'Why are you drawing attention to this?' And he was feeling this layer of shame.”

It was a natural reaction, which Yang said was not that different from how she would’ve reacted when she was a child. “I’m like no. You know, we’ve evolved, and we no longer need to be covering this up with shame," she explained, adding, "That’s what I did. I would often brush it under the rug."

She went on to post the video and said she wanted people to understand that these incidents were really happening. She noted that often when she shared such events with people she knew, even in the Bay Area, people reacted with some amount of doubt. Folks seemed incredulous that these acts of xenophobia were actually occurring around them.

“If this is happening to me, it’s happening to other people of color,” Yang said. “I wanted people to understand that this is truly happening and the comments that politicians make and all the xenophobia absolutely affects our children, and then they go ahead and they do the same thing,” she explained, which offered yet more reason for her commitment to open up dialogue about racism and prejudice.

Race has been a critical theme in her books, as well as an integral part of her lessons as a writing instructor. “I write a lot about race identity and the immigrant experience, so these things come up again and again. When we get to a discussion about character and motivation, those themes always come out,” she explained.

Yang’s books have been interwoven with stories drawn from her own life. She was 6 when she and her family immigrated from China and moved to Los Angeles. At the young age of 13, she went to college, graduating from UC Berkeley, before attending Harvard Law when she was 17.

With all of her successes along with the progressive landscape of the Bay Area, she acknowledged that even she naively thought she might be in a place where she and her kids were somewhat insulated from hateful rhetoric and xenophobic attitudes.

“I thought I could avoid having some of these conversations in 2020 with my kids, but you can't,” Yang said, noting that the reality of where the country stood today when it came to racism has been eye-opening and somewhat traumatic.

“I could still get hit with any of these comments… and feel so small, and that’s when you realize that it's very much alive. It can affect us in a big way.”

Her latest book "Parachutes," which came out last month, was her debut young adult (YA) novel. In it, she explored the modern immigrant experience with characters who face racism and other struggles. A resonating theme from the book was about using your voice as your armor.

It's been a message that she as an Asian-American woman has also chosen to live by, as she empowered and encouraged others to take up that armor as well.

Yang said for many Asian-Americans, "sometimes it’s hard for us to speak out and say, we’re all experiencing racism,” and she challenged people to use their voices to ask, "What do we do about it collectively?”

Kelly Yang with 10-year- old son, 7-year-old daughter and family dog.