Death rate at Santa Rita exceeds nation's largest jail system as critics call for reform

Alameda County sheriff acknowledges one death is too many

Santa Rita, which has had an average daily population of 2,930 inmates over the last five years, is six times smaller than Los Angeles County jail system, the largest in the nation with a five-year average of 17,595. But it has a 50-percent higher jail death rate

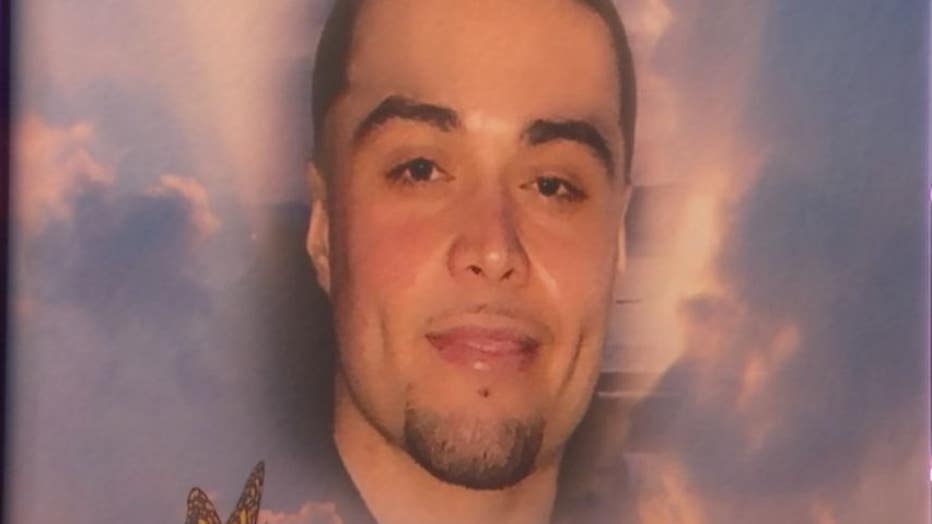

DUBLIN, Calif. - Vanessa Reyes said the visit with her husband at Santa Rita Jail this summer seemed no different than any other. Before leaving, the Pittsburg mother lingered by the jail’s glass partition, hating to say goodbye to her “sweet, funny Ray.”

They talked the next morning by phone. ‘“OK, I love you,’” she remembers Raymond Reyes Jr. saying before hanging up. ‘“I’m going to call you back.’”

Vanessa Reyes never talked to her husband again.

Three hours after their last call on July 24, an email alert from the jail said Reyes had been “released.” It took five more hours for Vanessa Reyes to find out what really happened.

“They walked in his cell and they found him there… Dead,” Vanessa Reyes said through tears during an interview with 2 Investigates earlier this month.

Eventually, Alameda County sheriff’s deputies told her that her 22-year-old husband from Hayward -- the father to their 4-month-old baby -- had committed suicide.

She’s tried in vain to find out exactly what happened. “They don’t give us no answers,” she said. “I left multiple messages. Nobody has called me back.”

A closer look at the 40 inmates who have died at Santa Rita Jail

Raymond Reyes was kept in isolation for 19 days. He hung himself after seeming OK to his wife on a phone call the day before.

Reyes is at least the 40th known inmate to die at Santa Rita Jail in Dublin since Jan. 1, 2014, and at least the fifth this year alone, according to data 2 Investigates compiled from autopsies reviewed through Public Records Act requests and additional reporting.

Reyes was one of at least 14 people to have committed suicide in that time period. And of those suicides, he is also one of at least 11 inmates — or nearly 80 percent — who were also kept in some type of isolated confinement with limited or no access to the outdoors and human interaction, according to the analysis of autopsies, police reports and federal lawsuits.

To compare, Santa Rita, which has had an average daily population of 2,930 inmates over the last five years, is six times smaller than Los Angeles County jail system, the largest in the nation with a five-year average of 17,595. But it has a 50-percent higher jail death rate: There were 13.6 deaths per 1,000 inmates at Santa Rita compared to 8.9 deaths in LA over a five-year period using the most recent data available.

(*EDITOR'S NOTE: Santa Rita jail leadership contend the total number of inmate deaths is actually 38. But the coroner's report of one of those inmates, Paul Wilbert Lee, shows that he experienced a seizure in cell T-2, despite the Sheriff's Office insisting he was never booked into jail. The second inmate in question, Christian Madrigal, hanged himself inside his cell with the very same chain that was used to restrain him to a door. The Sheriff's Office contents that his death was not "in-custody" because he was released under a "compassionate release" program and died at a hospital. There are also two additional inmate deaths, Christopher Thomas and Michael Herman, that the Sheriff's Department is not counting, which would ultimately bring KTVU's total to 42. Despite the county coroner's office confirming that Thomas and Herman are classified as "in-custody deaths," the autopsy reports are not yet publicly available so 2 Investigates was unable to independently verify the circumstances for this report.)

Women sue Santa Rita over treatment; sheriff says it's the "best big jail in the nation"

“The numbers are disproportionate in Alameda County,” said civil rights attorney Ben Nisenbaum, who along with John Burris, is representing the Reyes family. “And that’s disturbing.”

In Reyes’ case, he had been in Santa Rita since February after violating parole stemming from a prior burglary. He had been in isolation for 19 days before his death, his wife said. He was there, she said, because he suffers from social emotional disorder. Friend and former inmate, Jamario Harris, said he heard Reyes begging the guards to be let out. "He wasn't getting any yard time," Harris said. "He wasn't getting air. He told them, 'I can't be in this room. I can't be like this.' "

2 Investigates: Inmates' death at Santa Rita raises questions about private medical company

These suicides and jail deaths are raising questions at the highest levels. 2 Investigates has learned that the U.S. Department of Justice Civil Rights Division’s special litigation “Alameda Team” has been investigating the mental health system at Santa Rita since January 2017. The DOJ team’s most recent visit to Santa Rita was in July.

Sheriff Gregory Ahern is well aware of the issues and the investigations. And he promised he is trying to fix it.

“We know we’re getting criticized,” he told KTVU on a tour of the jail on Friday. “If you were an athlete, and if you got criticized for the speed you ran, you’d go out and improve your speed, right?”

He added somberly: “We strive for zero deaths here.”

Ahern said that his deputies go through “great pains to keep people alive” at the jail. While staff does not keep track of how many suicide attempts deputies stop, he said that they do keep track of one life-saving metric: jail staff have used the opioid overdose drug, Narcan, on inmates at Santa Rita 10 times.

Inmate deaths weigh heavily on everyone, Ahern said.

“Every person along the chain is affected," he said. "It affects the individual's family, their relatives, their friends that are out and the other inmates. It’s very impactful here when a tragedy occurs.”

Alameda County Sheriff Greg Ahern (left) said inmate deaths affect everyone.

As for isolation, Ahern acknowledged that human beings need more than an hour a day to be let outside and have contact with others.

“We do not like to keep people in those cells for any length of time,” he said. “We want to make sure they are out of their cells as much as possible. They earn their right to be out of the cell.”

Along the tour, Ahern also described a program launched in 2018 aimed at reducing the number of inmates kept alone in Administrative Separation at Santa Rita jail, called Maximum Separation, or "Max Sep." So far, jail staff say, the small program has about 150 inmates who have signed contracts promising they won’t get into fights. They are then allowed more group time together than if they were housed alone.

Of course, sometimes inmates have to be kept apart, he said. About half of the inmates need some sort of "special handling," because they have mental health issues, are in gangs, or might face repercussions from others because of the crime they are accused of, such as child molestation, as examples, Ahern said.

In theory, Ahern said he is all for adding more group counseling sessions for inmates with mental health issues. But in practice, he said, that can create security issues. He pointed toward the upcoming construction of a new $54-million mental health facility expected to be completed by 2023. In the new facility, counselors could meet in more private settings with inmates, but Ahern acknowledged the money only covers construction, and he still needs funding to cover counseling costs. “We need more behavioral health staff employed here at the jail,” he said. “I’d like to see a 24-hour a day behavioral health response.”

But he said most of the issues at the jail have to do with money -- and the lack of it.

“Every time I get a chance,” he said, “I tell people we're understaffed and underfunded. I tell the media that and I'm telling you that today. I tell the Board of Supervisors that and now we're having experts come in and validate exactly that point.”

READ: Calif. senator calls for audit of Santa Rita and sheriff

It’s hard to get a complete grasp on the financial situation at Santa Rita, and how much money is devoted to mental health counselors, medication and other health services. What is known is that the sheriff's budget has gone up by $144 million over the last decade for a 2019 total of $443 million as the jail population has gone down, according to a letter state Sen. Nancy Skinner wrote to Ahern in February, calling for an audit.

"Our population count has gone down, which has caused a lot of concerns," said Ahern. "Why has the population gone down, but your money has increased for the cost? A lot of advocates wonder why that is the case."

Ahern said what's going on at the jail is mirroring the mental health crisis gripping the Bay Area. "The people that come into our custody have very complex crises in their life right now," he said. "It's not just one thing, not just crime, it's health, it's drugs, it's alcohol, it's mental health issues, et cetera."

Ahern also said that he and the jail often get unfairly maligned. He took special care to point out how clean the premises were, how fall decorations were up on the walls and how shiny the doorknobs were.

“Some of the issues that are brought to us,” Ahern said, “we think are exaggerated and not accurate.”

The link between isolation and inmate suicides is not a new phenomenon. According to a 2014 study in the American Journal of Public Health, isolated inmates were three times more likely to self-harm. Those researchers found that a best practice was to move mentally ill people out of the more “punitive” solitary situation and into a more therapeutic setting.

Civil rights attorneys John Burris (left) and Ben Nisenbaum are representing several plaintiffs who are suing Santa Rita Jail.

2 Investigates decided to take an unprecedented look at Santa Rita, examining the records to learn who was dying and why.

The analysis involved more than 1,000 pages of Alameda County Sheriff’s coroner’s reports -- along with those in three other Bay Area counties -- a review of federal lawsuits, news articles and arrest records, plus additional interviews with lawyers and relatives.

The investigation revealed:

Some of the autopsies specifically mentioned suicidal inmates being housed in isolated conditions. Logan Masterson killed himself on April 8, 2018 after he was placed into a “safety cell” and then an isolation cell “without proper medical attention” until he hung himself, a federal lawsuit alleges. The jail staff were “deliberately indifferent” to his “medical needs and safety,” according to the suit, “and failed to provide necessary medical or psychiatric care” to prevent him from attempting suicide.

At least 20 of the 40 inmates who died — or 50 percent — were kept in some form of isolation. The sheriff insists there is no such thing as "solitary confinement" at Santa Rita. But there are environments where inmates are left mostly alone, without access to the outdoors, or program time for up to 23 hours a day, according to plaintiffs in a lawsuit and the lawyers representing them who have toured the facility several times. These units can be called administrative segregation or administrative separation where inmates may be allowed out to make a phone call, shower or see sunshine for only one hour every two days, or in the “behavioral health” unit with limited access to a yard or programs, as described in class-action federal lawsuit filed in 2018. Another type of cell in question is called a "safety cells. " By law, these cells are not allowed to have toilets and are meant to protect inmates from killing themselves. But plaintiffs' attorneys allege some inmates are kept in these close confines for up to three days while these rooms should only be used for an hour or two at most. According to the lawsuit, suicidal prisoners in safety cells are stripped naked, given smocks to cover themselves and only have a hole in the ground to go to the bathroom. “That means they have to eat and sleep on the same floor that they must also urinate and defecate on,” the suit alleges. The county responded in filings that “toilet paper is available upon request,” and that the smocks are called “modesty garments.”

Some suicidal inmates aren’t letting deputies know their states of mind, according to the lawsuit. “Due to understaffing, poor management and lack of treatment space, Alameda County relies almost entirely on the unconstitutional use of isolation to manage prisoners, including prisoners with significant disabilities and mental health needs, resulting in horrific suffering,” the suit states. “Conditions are so bad, that prisoners have stopped reporting suicidal feelings to staff in order to avoid being thrown into safety cells.”

A special purpose cell at Santa Rita Jail. September 2019

Alameda County’s Santa Rita Jail also has the highest death rate compared to other Bay Area jail systems.

San Francisco, with 1,200 inmates in three jails, reported 11 in-custody deaths since 2014 at a rate of 9.1 deaths per 1,000 inmates, nine of which were natural and two were suicides. The two suicides occurred before 2015. The city’s Department of Health, which spends $36 million a year on jail health services, has a mandate from the Board of Supervisors that jail health care must be as good as the health care provided in the rest of the city, such as Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital. That budget includes 165 full-time employees, with 30 on the behavioral health team and nursing staff in the jails 24/7.

Contra Costa County, with an average of 1,485 inmates since 2014, reported 18 deaths during the same time period at a rate of 12.1 deaths per 1,000 inmates. Contra Costa County has the second-highest jail death per capita rate in the Bay Area and an even higher suicide rate than Alameda County. At least eight of the deaths - or 44 percent - were suicides, a review of autopsies revealed. Contra Costa County does not list where inmates were being held in its coroner’s reports, so it wasn’t immediately clear which of those inmates were kept in any form of isolation.

San Mateo County, with 1,200 inmates, reported six jail deaths since 2014 at a jail death rate of 5 deaths per 1,000 inmates. None were suicides.

In Alameda County, deaths occurred among a variety of ethnic groups as well as the young and the old. The youngest of the inmates was 20 years old. The oldest was 70. The inmates who died were white, Black, East Indian, Vietnamese and Mexican. Two women and one transgender woman were included in this count. The occupations of those who died included: A baker, screen writer, mechanic, Marine, homemaker, gas station attendant, laborer, to name some. The crimes they were suspected of committed include burglary, drug and firearm possession, domestic violence, child abuse and attempted murder.

But it doesn’t matter what someone was arrested for or convicted of, said Jose Bernal, senior organizer at the Ella Baker Center for Human Rights, a vocal critic of the sheriff. Everyone by law, he said, must be afforded their basic, constitutional rights. It should also be noted that on average in the United States, 77 percent of inmates in local jails have not been convicted, according to a snapshot compiled this year by the Prison Policy Initiative. At Santa Rita jail, Ahern says the number of pre-sentenced inmates is about 65- to 75-percent.

For nearly two years, Bernal has been pushing for an outside auditor to review the jail’s finances and the sheriff’s performance. And his group has also been lobbying for the sheriff to be separate from the coroner’s office, which is the case in San Francisco and Los Angeles, so that there can be an independent review of each death in jail.

“It doesn’t ensure trust knowing that the same person, or the same department, where (a death) happened is also investigating from start to finish,” Bernal said.

Alameda County Supervisor Wilma Chan declined an interview citing the pending lawsuit. The remaining supervisors did not respond by email request to discuss the overall mental health situation and allocation of money on mental health care at the jail.

But in court filings, Alameda County counsel argued that the number of in-custody deaths — including suicides — at Santa Rita have “been steadily trending downward for the past five years.” And while the county acknowledged that administrative segregation cells are used for those who commit serious rule violations, the county’s attorneys asserted that it’s very “rare” to place inmates there. In addition, while the county acknowledged that each of the plaintiffs had been in isolation at some points, in general, inmates are moved and housed in different areas depending on the circumstances during their stays.

In each of the specific cases, the county said they couldn’t verify, for example, if an inmate was indeed shaking and crying and or exhibiting mental health problems. But in general, the county attorneys argued that they are “not required to admit or deny” whether the plaintiffs who filed suit are disabled or not and whether they are required to make accommodations for them.

Some jail reform advocates say that change could come to Santa Rita whether the sheriff willingly agrees to it or not.

“It may be that federal oversight will be necessary if the sheriff himself doesn't take this more seriously and reduce these numbers,” said Burris, who is also one of the lawyers who sued Oakland after the infamous Riders police scandal. As a result of that suit, OPD has been under federal oversight for the last 16 years.

READ: Family plans to sue Fremont police, sheriff over son's possible suicide

Reform could also be made through the class action lawsuit, said attorney Kara Janssen.

Her firm, Rosen, Bien, Galvan and Grunfeld, is demanding that the sheriff and county stop the use of “cruel and unusual” isolation cells and provide adequate mental health care and reasonable accommodations to prisoners with disabilities. Her firm is not seeking any punitive damages. Rather, her firm and the county have agreed to a panel of experts who are now evaluating the jail.

Since June, Dr. James Austin, Dr. Kerry Hughes, Terri McDonald and Michael Brady have been inspecting Santa Rita, taking photos of the cells and reviewing documents, Janssen said. There are mediation dates scheduled through December 2019 to see if any type of reforms can be made, which would avert the need for a trial.

“We agree this is a hard issue,” Janssen said. “And the jail can’t fix everything. But many of these people should not be incarcerated. The jail is not set up for people in a mental health crisis. There is a large issue for the county to create a system of connecting these people with services and putting them in isolation isn’t the answer.

For now, many families, like the Reyes’ are left grieving and wondering just what happened inside the walls of Santa Rita Jail.

Raymond Reyes had a troubled life, getting mixed up with the wrong crowd, and struggling with his mental health, his family said. But he was more than a just a rap sheet. He loved to joke around, sing, and “could light up the room with a smile,” said his mother, Yasmin Reyes. And he would have been a wonderful father to his son, also named Raymond, who is the spitting image of his brown-eyed dad.

“They said they ruled it a suicide,” his sister, Reanna Reyes said. “But for me, in my heart, I don’t feel like he did that. He has a 4-month-old son. All he ever wanted was to have a family.”

Yasmin Reyes holds her grandson, Raymond Reyes, named after his father, who killed himself on July 24, 2019 at Santa Rita Jail.

WHO IS DYING AT SANTA RITA, BY THE NUMBERS:

The 2 Investigates analysis, which included a review of hundreds of pages of coroner's reports, lawsuits and news articles, arrest records, and interviews with family members and experts, also revealed:

Since Jan. 1, 2014, at least 40 inmates have died at Santa Rita Jail.

Of those, at least 14 people committed suicide. Of the suicides, at least 11 were kept in some form of isolation before they killed themselves.

Of the 40 inmates, 20 were kept in some form of isolation.

In at least three of the deaths — Dujuan Armstrong, Christian Madrigal and Nestor Aguilar — a physical restraint, called a WRAP, was used. In Aguilar’s case, a WRAP and a spit mask were used to restrain an inmate.

One person who died at Santa Rita, Melvin Stubbs, had been mistakenly arrested for the death of his wife. Her death turned out to be natural, and Stubbs, who suffered from diabetes, died of cardiac failure.

At least 40 inmates have died in Santa Rita jail since 2014.

TYPES OF ISOLATION AT SANTA RITA:

Administrative Separation: About 10 percent of inmates are housed here. They are housed alone in a cell and are allowed outside for a limited amount of time for recreation also alone, depriving them of any social interaction.

Disciplinary Isolation: Punitive segregation from the general jail population and restricted privileges for inmates who commit “serious rule violations.” Inmates can leave their cells for one hour a day, five days a week. There is no cap on the use of disciplinary isolation. Inmates may be held for more than 30 days here for a single violation.

Behavioral Health/ Outpatient Health Unit/Unit 9: Inmates who are “mentally disordered” and those on suicide watch are housed in these “special management units,” maximum security units, which are “highly restrictive” cells that provide “significantly reduced, or non-existent” access to educational and rehabilitative programming compared to non-disabled inmates. Inmates with psychiatric disabilities in these units may receive as little as five hours of time outside their cell per week. Inmates on suicide watch cannot have socks or underwear. One inmate, Ashok Babu, who suffers from schizophrenia, was placed on suicide watch in one of these units for 10 months in 2017. During that time, he had no access to the outside yard or day room facilities, a federal lawsuit alleges. He had no access to books or classes. He continued to hear voices and feel suicidal and depressed. His mental health evaluations were conducted through his closed cell door or at his cell door with the door open, according to a class-action federal lawsuit. On a recent tour of Unit 9, however, KTVU witnessed multiple inmates on phones, watching TV and in the common room together.

Safety cells: Suicidal inmates are often put in safety cells, where inmates are supposed to be kept for short periods of time. The cells have no toilets and no sinks per state law. Inmates placed in safety cells are stripped naked and dressed in a tear-proof smock. Inmates defecate through a grate and have to ask for toilet paper, according to a federal lawsuit. “You can imagine how often that happens,” said plaintiff's attorney, Kara Janssen. “That is a horrible way to respond to someone who is suicidal.” The county, in court records, contend that the smocks are “modesty garments” and that toilet paper is given upon request. On a tour through the jail, KTVU asked to see a safety cell just outside the Behavioral Unit 9 entrance. Deputies did show what they described as a safety cell with toilets and sinks and lights. The small room had no bed, and deputies said that inmates were sometimes put into these rooms if they were fighting and deputies were urged to get them back into their regular housing unit as quickly as possible after investigation of the incident was complete.

Maximum Separation or “Max Sep:” A new program Sheriff Greg Ahern started in 2018 with about 150 inmates who used to be kept in administrative separation, allowing them to have more human contact and free time if they sign a contract promising they will not fight with the other inmates they are co-mingled with during recreation time.

Sources: Masterson v. Alameda County, Gregory Ahern et al. and Babu v. Alameda County, Gregory Ahern, Carol Burton, interview with Sheriff Gregory Ahern.