Edited body camera footage raises questions about police accountability

VALLEJO, Calif. - Police deadly force incidents are increasingly being captured on video thanks to the proliferation of body-worn cameras. And a recent California law compels departments to release the footage within 45 days.

But some law enforcement agencies edit the footage, spinning a favorable narrative and raising questions about police transparency and accountability.

The city of Vallejo recently settled a civil lawsuit in the killing of Ronell Foster for $5.7 million – even though the police department defended the shooting and doctored the body-camera footage to back up their account of the events.

“The camera is a potent weapon, but it has to be used properly and with transparency,” said John Burris, a Bay Area civil rights attorney who represented Foster’s family. “You do not need the edited view and narration on the part of police.”

Heavily edited police videos are coming under renewed scrutiny amid increasing tensions between law enforcement and the communities they’re assigned to protect, following the recent high-profile killing of George Floyd and other people of color.

Editing videos in some cases, however, can provide important context, like if a person shoots first at officers and it’s not overtly apparent in the real-time often-shaky body-camera footage.

But in the Foster case, and in the Vallejo police killing of Willie McCoy one year later, many activists say the police department distorted the facts with their video edits and narrative comments.

Foster was riding a bike erratically without a light on Caroline Street in Vallejo when Officer Ryan McMahon tried to stop him in February 2018.

Foster fled, and ran into an alley where a scuffle broke out. McMahon shot him multiple times.

Foster’s family and many in the community were stunned when Vallejo police released a heavily edited version of the body camera footage.

It was slowed down. Text was added which didn’t necessarily match what the video showed, and it omitted that McMahon had shot foster multiple times in the back, and in the back of his head.

“It shows me my nephew being murdered in cold blood,” Foster’s uncle, Al Polk, said in a recent interview at the small alley where his nephew was killed. “By no means did he deserve to die in the streets and the hand of someone who’s supposed to protect and serve.”

McMahon was cleared by the Solano County District Attorney. But this month, the city of Vallejo settled the civil lawsuit with Foster’s family – one of the biggest payouts for a police killing in Bay Area history.

“To me, they’re admitting guilt. Why would you give someone almost $6 million if you didn’t think something was wrong?” Polk asked rhetorically.

After the shooting, McMahon was back on patrol, and one year later he was one of six officers involved in the controversial killing of McCoy.

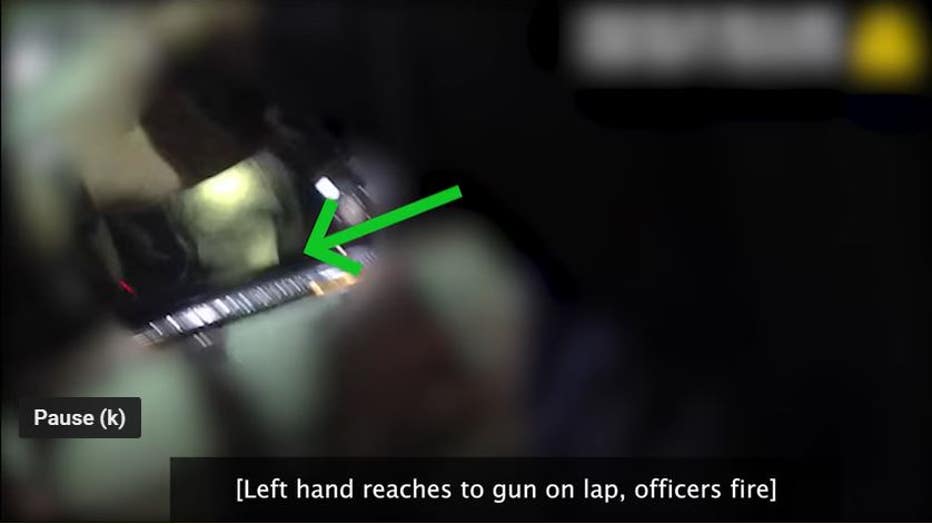

Police shot McCoy moments after he awoke while unconscious behind the wheel of a car with a gun in his lap.

In that case, Valleo police slowed the footage down, added text and arrows, distorting how things played out in real-time.

At the time, the shooting was supposedly still under investigation.

“When a case is under investigation, that investigation should not include editing of independent evidence,” Burris said.

McMahon’s attorney did return requests seeking comment.

Vallejo Police Chief Shawny Williams was hired after the shootings. He sought to fire McMahon and has since placed him on paid administrative leave.

He said while he’s in charge, the department won’t be manipulating body-worn camera footage to present their side of the story.

“What our citizens deserve is the absolute facts in those cases,” he said.

Vallejo isn’t the only department that has edited footage of police shootings. In April, San Leandro police released an edited video of an officer fatally shooting Steven Taylor inside a Walmart.

The video didn’t omit major information except for blurring the officers’ names and badge numbers. But the department waited nearly two weeks to release the full raw footage.

The Alameda County District Attorney’s Office has since charged Officer Jason Fletcher with voluntary manslaughter in the shooting.

San Leandro Police Chief Jeff Tudor told KTVU he rushed to put out the edited footage because cell phone video was already posted online and he wanted people to know exactly what happened.

He said the department needed more time to redact the raw footage.

KTVU filed numerous public records requests with police departments around the Bay Area to see who was editing the videos. In some cases, law enforcement agencies hire outside firms to put videos together, in others they have civilian employees who do the work in-house.

KTVU requested invoices from any editing companies who may have been paid to create the Foster and McCoy videos. The city of Vallejo said there were none.

But Vallejo police recently contracted Laura Cole of Cole Pro Media. Her company edits police critical incident videos. She said her staff didn’t work on the Foster or McCoy videos

“It’s extremely important to us that there’s no spin in any of the critical incident videos that we put together,” Cole said in an interview with KTVU.

She said that context is crucial because it can help the public better understand what happened.

“Context is hearing that 911 call," Cole said. "It’s, was there any surveillance video? Was there dashcam video that goes along with the body cam footage? Is there cell phone footage? What did witnesses say?”

She said her company works to help police be transparent and accountable and that includes police departments not editing videos themselves and releasing the raw video at the same time if possible.

“It shouldn’t matter if this is something that makes them look good, or look bad. This is about the facts,” she said.

For Foster’s uncle, the facts couldn’t be any clearer.

“These officers need to be held accountable or it’s going to continue,” he said.

Evan Sernoffsky is an investigative reporter for KTVU. Email Evan at evan.sernoffsky@foxtv.com and follow him on Twitter @EvanSernoffsky