Oakland issued $1.3M in illegal dumping citations - and collected hardly anything

Oakland issued $1.3M in illegal dumping citations - and collected hardly anything

Since 2021, Oakland has issued nearly 3,000 illegal dumping citations totaling about $1.3 million but only collected about $109,000 – or 11% – of those fines.

OAKLAND, Calif. - Piles of trash, box spring mattresses, old blenders and other garbage are common sights around Oakland, as the issue of illegal dumping has perplexed the city for years.

The unsightly scenes became even worse during the pandemic, and Oakland city officials began to find new ways to crack down on people dumping their trash on city streets by installing new cameras and issuing citations with more zeal.

But a KTVU inquiry and investigation shows that many of these efforts have been underwhelming and inefficient.

Since 2021, the city of Oakland has issued nearly 3,000 illegal dumping citations totaling about $1.3 million, data compiled by the city shows.

However, Oakland has only collected about $109,000 – or 11% – of those fines, according to numbers provided by the Department of Public Works at the request of KTVU.

In all of Oakland's messaging about illegal dumping, the number of citations is often touted. But the money that's been collected through these fines - or, rather, not collected – has never been reported publicly before.

Josh Rowan, the Department of Transportation director who was recently put in charge of Public Works as well, said he had no idea about this until this news organization brought it to his attention.

"I was surprised," Rowan said on Monday. "It's a number we're not proud of. This is pitiful."

Last year, Oakland crews picked up 20 million pounds – 10,000 tons – of illegally dumped trash.

"I've never seen volume like this," Rowan said. "In Oakland, we do have bigger challenges than in other cities."

Rowan said the problem is complex, and the city is exploring how to fix some of the issues by installing more cameras, redesigning city streets to make it harder to dump, increasing the fine fees and doing a better job of collecting money from the fines.

Oakland has issued nearly 3,000 illegal dumping citations and collected only 11% of the total amount.

ANALYSIS OF DATA

KTVU poured through hundreds of illegal dumping data entries of citations and appeals released through a California Public Records Request.

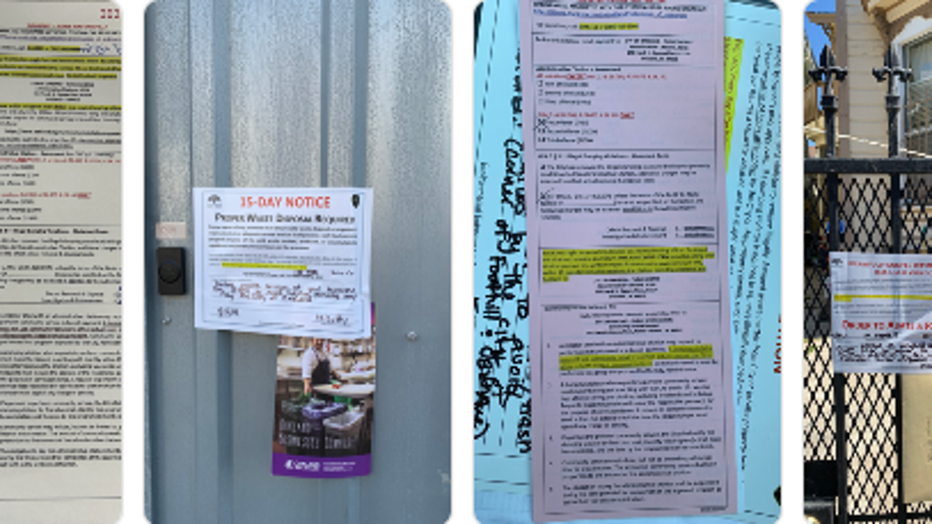

The analysis revealed that enforcement officers spent a lot of time writing tickets by hand, sticking them on doors or mailing them, only to have a large percentage of people appeal those citations.

There are 53 employees in the illegal dumping unit and five environmental enforcement officers patrolling a city of 78 square miles.

"Pay the fine!," officer A.L. Watson wrote to someone on 26th and Peralta streets. "You were captured on camera illegally dumping trash and debris."

A total of 465 recipients of those citations appealed by writing letters to the city. All but 12 appeals were granted, the analysis shows.

People successfully argued that the garbage found on the street wasn't theirs. Most blamed homeless people for rifling through their trash and scattering it throughout the neighborhood.

COMMUNITY RESPONSE

Various communities respond to the dumping in various ways.

In Arcadia Park, garbage has been known to block the streets and has frustrated and disappointed its East Oakland residents.

Rochelle Baxter, president of the homeowner's association there, said she and others have complained to the city about the illegal dumping and routinely report these acts on the city's "See, Click, Fix" site.

"But as many times as we have tried to have this matter addressed with the city, we don’t get anywhere, and we’re just tired, like, we’re really tired," she told KTVU in October.

Other neighborhoods, like the business owners at Jack London Square, have pooled their money together to hire crews to clean up the junk.

In fact, Savlan Hauser, executive director of the Jack London Improvement District, said most of their annual $1.5 million is spent on cleaning the 83 square blocks that line the Oakland estuary a year. Last year, her 12 ambassadors picked up 370,000 pounds of trash - a 30% increase from the prior year.

"We have to deploy our resources really intelligently where the needs are greatest," Hauser said.

Like many, Hauser believes using cameras can help curb the problem by catching perpetrators.

"I think surveillance is an important piece of infrastructure that communities can have to empower us to keep our neighborhoods safer," she said on Monday. "We can show that people care and are watching and are not going to just stand by while people dump or vandalize our neighborhoods."

Oakland has created its first "bollard city" along Courtland Creek to deter illegal dumping. Dec. 30, 2024

CAMERAS AREN'T A PANACEA

The city of Oakland has been touting cameras, too.

In February 2022, Oakland set up 10 cameras at known illegal dumping hot spots, including 21st Avenue and Solano Way, in the hopes of building cases against offenders.

In October, Oakland announced it was adding 15 new cameras with automated license plate technology.

Rowan said the city has 30 cameras and has plans to add six more.

But the cameras are far from a panacea.

During the first year of the camera program, the technology "cooled" the number of illegal dumpings by about half at eight locations, according to a city report in August. But by the second year, illegal dumpings "notably increased," the city found.

From April 2023 to March 2024, surveillance cameras recorded 457 instances of illegal dumping in Oakland, resulting in only 59 instances – or 13% – resulting in citations being issued, the city report noted.

That's because, in many cases, either the cameras don't read the license plate numbers of the vehicles dropping off the garbage, or the drivers are savvy enough to cover their license plates. In a quarter of the cases, the car had no license plate, the city found.

Bottom line: The city found that data from the cameras didn't help catch a perpetrator 55% of the time.

Plus, cameras are essentially non-effective when it comes to people dumping if they're not in cars at all, the city noted.

The initial city cost to install cameras was $85,000 in 2022.

The projected ongoing costs of running the illegal dumping surveillance program with the new license plate reader technology cost roughly $425,000 for the fiscal year 2024-2025.

Despite all this, Rowan said he felt that the cameras are still one important tool to help either deter dumpers from going to a certain location, or help police catch the perpetrators after the fact.

"I don't expect them to solve all the problems," Rowan said of the cameras. "But it is a tool we need."

Raya Man is a Jack London district ambassador. Dec. 30, 2024

SHIFTING COLLECTIONS

On top of the camera issue, Oakland has had a difficult time actually collecting the money it's owed.

Rowan said it's hard for the Department of Public Works to both issue the citations and be in charge of collecting the money, too.

He said he'd like to shift the collections' aspect to the Department of Finance.

Currently, a first-time offense for dumping costs $750, and a third-time offense costs $1,500.

Rowan said the city is considering upping the fines.

Trash along Courtland Avenue in Oakland. Dec. 30, 2024

ENVIRONMENTAL DESIGN INTERVENTIONS

Rowan would also like to be proactive in deterring illegal dumpers.

His crew has just finished building what he calls "bollard city" along Courtland Creek near the Allendale and Maxwell Park neighborhoods.

The bollards, or tall yellow poles, line the entrance to the creek, which make it harder for a big truck or even a car to pull up and dispose of waste in such a small area.

He said this idea came about after some community members demanded the area get cleaned up; it used to be home to a chop shop.

A police officer directed the community to the Department of Transportation, which ended up creating this new environmental design, Rowan said.

One neighbor said she's noticed less trash in the area since the bollards went up about a month ago.

Rowan said these structures cost about $80,000, and he'd like to build between four and six a year.

WHAT ABOUT A FREE DUMPING SITE

Oakland touts on its website that it has "multiple cost-free options" for disposing of bulky junk.

But these options include just one free dropoff a year at the Davis Street Resource Recovery Complex in San Leandor, and one free curbside pickup a year.

The city also said it is not willing to add dumpsters to areas with high rates of illegal dumping, saying they would fill up quickly and invite more dumping.

Rowan said that the city should consider what creating a "transfer station" would entail – essentially a large slab of land where residents could drop off their garbage, for free or low cost, and then that garbage would be hauled away by the city.

But he added that this idea could be fraught with politics, mainly over how much it would cost and in which neighborhood it would be housed.

"Oakland should be open to all ideas," Rowan said. "Will we get rid of all the illegal trash? No. But we need to move the needle in a positive direction."

KTVU's Tom Vacar contributed to this report.