Oakland Police Commission sustains 1st case of racial profiling

Oakland Police Commission sustains 1st case of racial profiling

The investigative arm of the Oakland Police Commission has sustained its first case of racial profiling.

OAKLAND, Calif. - Mariano Contreras is no stranger to being stopped for his brown skin. As a Latino man who has lived in Oakland since 1975, police have stopped him driving down International Boulevard for no apparent reason. Officers have given him looks while walking around Lake Merritt.

But the 71-year-old print shop owner and community activist had never heard what he described as such blatant racial profiling from an Oakland police lieutenant before.

The lieutenant was trying to convince three Oakland Police Commissioners to allow OPD to buy more militarized equipment, like tear gas, to quell participants and spectators at sideshows – gatherings of hundreds of people and cars where drivers do stunts and tricks in empty lots or public intersections. Sometimes these gatherings erupt into gunfire and violence.

When questioned about why the tear gas and missile launchers were necessary at the sideshows, the lieutenant answered: "When we looked at our recent data for sideshows, a vast majority of the subjects engaging in sideshows are young adults, particularly male adults. Over 60% of folks who are engaging in sideshow activity were, South American, Latin culture, and stuff like that. All of these things directly conflict with our ability to maintain safety and take quick decisions when dealing with this extraordinarily dangerous behavior."

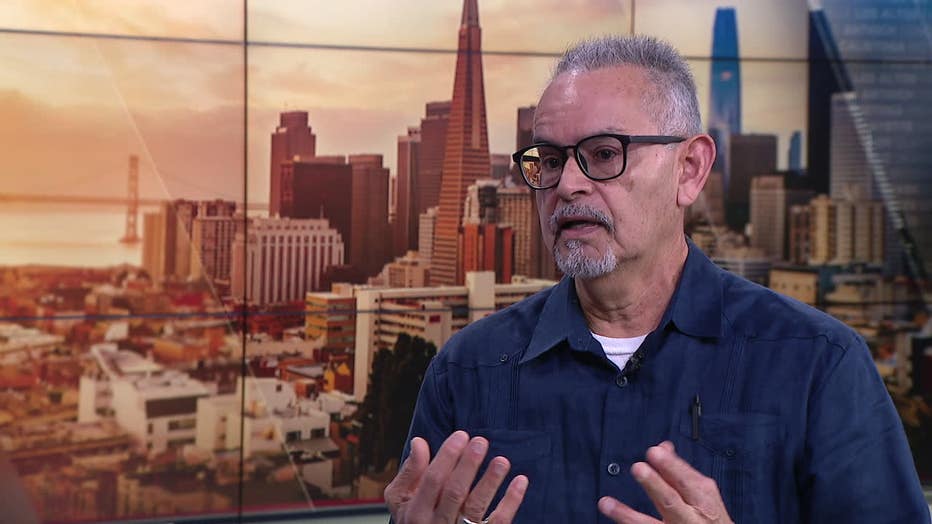

Mariano Contreras, a member of Oaklands Latino Task Force, is the driving force behind the first sustained case of police racial profiling.

The lieutenant also inferred that many of these sideshow attendees also carried guns.

One of the commissioners asked: What did 60% of the participants being Latino have to do with anything?

The lieutenant answered: English proficiency.

"It is very uncommon these days to not have any firearm usage at a sideshow," the lieutenant told the commissioners at a Militarized Equipment Ad Hoc meeting on Feb. 6, 2023.

Contreras, who attended the virtual meeting, immediately wanted to know whether this data existed.

"My ears went up," said Contreras, who has also been a longtime member of the Oakland Latino Task Force, later told the Oakland Police Commission. "And I said, ‘Wait a minute.’ This is racial profiling folks at its best.’

For Contreras, this type of sweeping attitude by law enforcement is quite concerning. He has yet to be given this data, despite asking for it multiple times.

"I can be perceived as dangerous because of who I am, the color of my skin," Contreras said. "But when this is done by someone who carries a gun and is authorized to use it on me, that becomes serious."

Raw video: White sedan fully engulfed after Oakland sideshow

Dramatic video of an Oakland sideshow shows a car fully engulfed in flames.

First sustained racial profiling complaint

Mac Muir, the executive director of the Community Police Review Agency – the investigative arm of the Oakland Police Commission – thought it was serious, too.

This year, his agency’s investigators found that Contreras’ complaint was valid and they "sustained" the case against the officer, which makes this the first sustained case of racial profiling in Oakland police history.

Muir did not mention Contreras by name and to this day will not speak about it in detail – only that his office sustained the first complaint of OPD racial profiling.

In fact, Muir's report is anonymous. But KTVU learned that Contreras was the person who filed the complaint because he openly shared this information, and he has the legal right to do so.

A sustained case means that the investigators found a "preponderance of evidence" that the conduct occurred and violated police department rules, regulations and policies.

Racial profiling, which is illegal in California, refers to the discriminatory practice by law enforcement officials of targeting people for suspicion of crime based on their race, ethnicity, religion or national origin.

Oakland has had a long history of racial profiling.

In 2003, OPD was sued by civil rights attorneys John Burris and Jim Chanin in the infamous "Riders" case after some officers planted drugs and beat Black men, which led to a federal consent decree that is still in effect, more than 20 years later.

In 2016, Stanford researchers were brought in to figure out why police in Oakland were stopping Black men four times more than white men during traffic stops.

Over the last two decades, racially motivated traffic stops have declined greatly and the use of excessive force has dropped significantly since that time.

But still, issues exist.

As recently as September, the Oakland Police Commission's Office of Inspector General found some of the police department's racial profiling and bias-based policing policies outdated.

While there was only one sustained finding of racial profiling, Muir’s agency sustained 65 other cases in 2023-2024 for such violations that include: compromising criminal cases, interfering with investigations, performance of duty, truthfulness, use of force and other categories.

Why this case is important

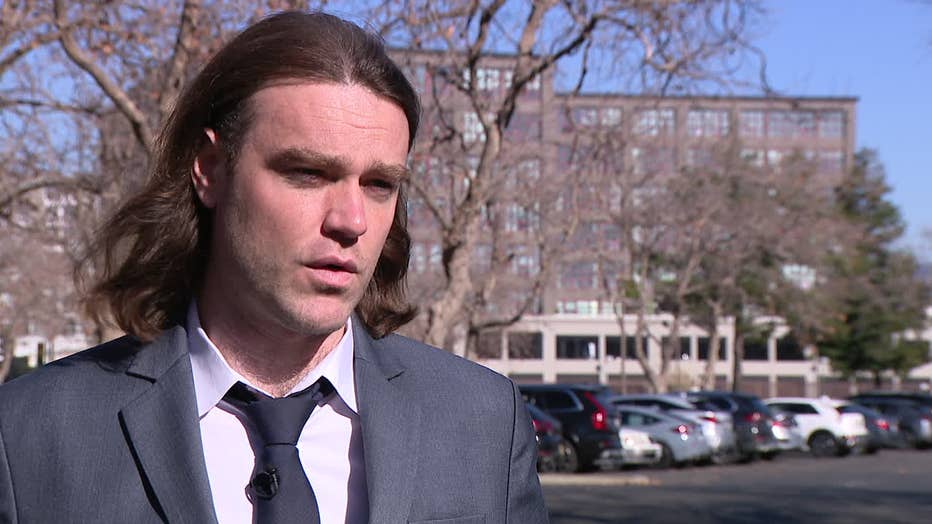

"I think it's important to the community that there's an understanding that its oversight entity is responsive to the policies and the concerns of the community," Muir said in a recent interview with KTVU. "And that there's a venue to speak to certain issues. And so I'd like to think that the community is able to see that we're doing good work and to the extent the law permits."

Muir said he especially wants Oakland residents to know that there is a due process of law for both citizens and officers, which he said will make Oakland safer for everyone.

Last year, his agency received about 250 complaints.

Muir encouraged anyone who feels they have been treated unfairly by the police to come forward – just like Contreras did.

"I think the folks that come to the police commission meetings, if they want to change or improve policing policies, the commission is highly receptive to the voices of the community and it’s designed that way," Muir said.

Mac Muir, the executive director of the Community Police Review Agency, the investigative arm of the Oakland Police Commission.

What the public still doesn't know

Despite the historic significance of this sustained finding, Oakland isn’t turning over any information related to Contreras' case – at least in the immediate future.

Under state law, SB 16, authored by former state Sen. Nancy Skinner (D-Berkeley), this case should be public, including the officer’s name, what discipline he or she received and the narrative of the situation.

The Right to Know Act II expanded on Skinner’s previous police misconduct transparency law, SB 1421, which mandates that sustained findings of racism or bias by law enforcement must be made public.

But the law has a loophole.

It allows officers to appeal the findings, and they often do. That means the case remains private until it reaches "final adjudication," which can often take three or four years.

Oakland does not release any of the sustained findings during this appeal process.

"The challenge here in California is that our cases are not disclosable until the end of the investigative process," Muir said. "So there can be appeals processes that prevent us from discussing our work."

He said it’s different in New York, Florida and Chicago, where much more police behavior is automatically made public.

KTVU was denied access to see the case after filing a public records request, so the inference is that the lieutenant involved is going through the appeal process.

For that reason, KTVU is choosing not to identify the lieutenant involved as, under normal circumstances, the case would normally not be public at this point.

What OPD has to say

The Oakland Police Department said it wouldn’t comment because it was a personnel matter.

The Oakland police union did not respond to two requests for comment.

Attorney Justin Buffington, who is representing the lieutenant in question, said it was too early in the process to talk, but he’d consider circling back at a more appropriate time.

Sustained findings usually come with some type of discipline, which can range from a write-up, more training, suspension or termination. But the details in this case aren’t known. Also, typically, the discipline isn’t meted out until the case goes through the yearslong appeals process.

The lieutenant is currently employed with OPD.

Gunfire erupts at Oakland sideshow, neighbors fed up with city leadership, "it seems like they don?t care."

An East Oakland neighborhood erupted into gunfire early Saturday morning amid an hour-long sideshow, and neighbors say police were nowhere to be found. Residents expressed fear that the next time, stray gunfire might enter an area home and hurt someone.

This isn’t a classic case of racial profiling

Contreras’ situation isn’t a classic case of racial profiling where an officer called him an ethnic slur, or where he was pulled over for Driving While Brown.

It’s a case that highlights a type of thinking held by law enforcement over an entire group.

And this attitude can be harmful, Contreras said.

"To this date, as far as I know, there's not any data compiled with statistics that can support that statement," Contreras said. "They observed it. They might have written a note on a piece of paper. And that information gets passed from one officer to another to another to another where then it becomes fact. And that fact, you know, is a dangerous one to assume. It becomes dangerous for people like me."

Contreras said if he’s stuck behind a sideshow on his way home – which he was recently – then a police officer might also believe that he’s part of the 60% of armed Latinos.

And if he’s questioned, Contreras said, he’d be put in handcuffs, and perhaps treated poorly because of this bias.

"When someone has a perception of someone else because of the color of their skin, it becomes concerning when it’s someone who can determine your mobility in a city like a law enforcement officer, a teacher or judge," Contreras said. "It determines how you go through life and what things you can do."

Mariano Contreras tells the Oakland Police Commission about his experience with racial profiling on April 13, 2023.

The impact of the police commission

This case once again shows the power of the civilian-led Oakland Police Commission to hold police accountable. In 2020, the commission fired then-Police Chief Anne Kirkpatrick. This year, the police commission chose the three candidates the mayor could choose from to hire the new police chief, Floyd Mitchell.

And Contreras wants people in Oakland to know the power of the commission.

"I want residents to listen to this story and feel confident that right now, we have a police commission that has the authority and independence to investigate a racial profiling complaint and there is an agency that has the wherewithal and authority to dig into it and not be dismissive," Contreras said.

Contreras hopes that his experience will prevent others from being racially profiled in the future.

He said he hopes that officers will pause before making similar types of prejudiced statements.

"When they stop me or my Oakland neighbor who doesn’t look like me, they’re going to treat us both the same," Contreras said. "So we will have equality under the law."

To learn more about the Community Police Review Agency or file a complaint, click here.