Patients, providers say UCSF affiliation with Children's Hospital means worse care for East Bay families

Patients, providers say UCSF affiliation with Children's Hospital means worse care for East Bay families

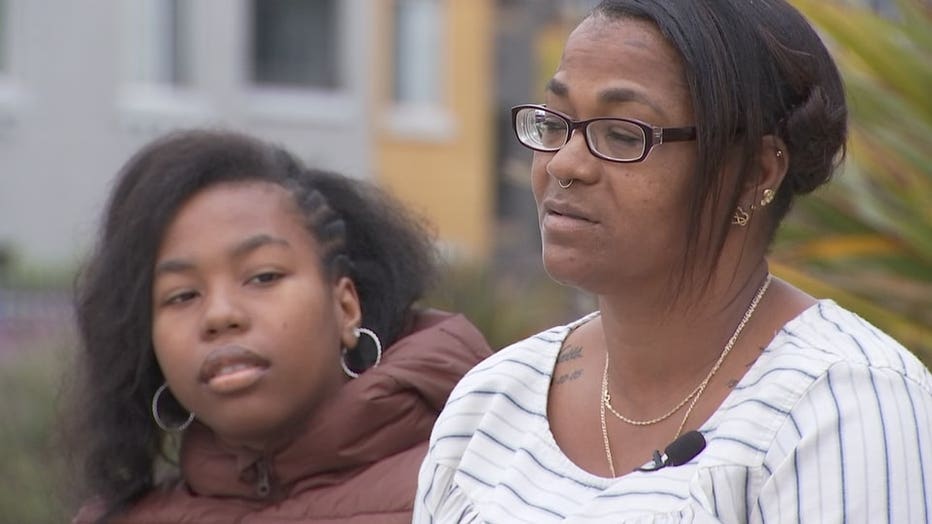

My'Wayna Stamps and her mother are among 30 sources whom KTVU interviewed, or listened to at public meetings, for this story. Their complaints have been building for the last seven years, ever since Salesforce CEO Mark Benioff poured $200 million into the partnership between the University of California San Francisco and Children’s Hospital Oakland. Brooks Jarosz reports

OAKLAND, Calif. - My’Wayna Stamps has been going to Children’s Hospital in Oakland since she was diagnosed with sickle cell anemia shortly after being born 14 years ago.

Back then, doctors and nurses treated her like family. She said she didn’t even know she was sick.

But last year, her long-term doctor quit last year because she felt the administration was not supporting holistic care and the sickle cell department. And in My'Wayna's opinion, the new medical team seems much more inexperienced and less knowledgeable.

And these changes, she said, seem to put her health in more jeopardy.

Recently, My'Wayna was told to wait in the ER with throbbing abdominal pain for an hour, when before, her mother would simply call her doctor to alert the team she was having a pain crisis so that a bed could be ready upon her arrival.

"I don’t like to go in," she said. "I’m scared."

Lawana Stamps was so upset with the lack of emotional care her daughter received that she filed a complaint and now is thinking for the first time of leaving the hospital that she has always loved and relied on.

"It's gone to hell in a hand basket," Stamps told KTVU in an interview this month. "It's traumatically worse. I don't know. It's like they just don't care."

Lawana Stamps (right) and her daughter, My'Wayna Stamps, 14, say that since UCSF affiliated with Children's Hospital in Oakland, their care has gone to "hell in a handbasket."

Patients, providers say care is worse for East Bay families

My'Wayna Stamps and her mother are among 30 sources whom KTVU interviewed, or listened to at public meetings, for this story. Their complaints have been building for the last seven years, ever since Salesforce CEO Mark Benioff poured $200 million into an affiliation between the University of California San Francisco and Children’s Hospital Oakland.

In a series of interviews over the course of three months, doctors, nurses, healthcare workers and patients allege that the 2014 UCSF merger with Children’s Hospital Oakland has made it worse for many patients in the East Bay. And that’s especially hard for these critics to reconcile at a hospital whose main mission for 100 years has been to care for every child in the same way, regardless of their family’s ability to pay.

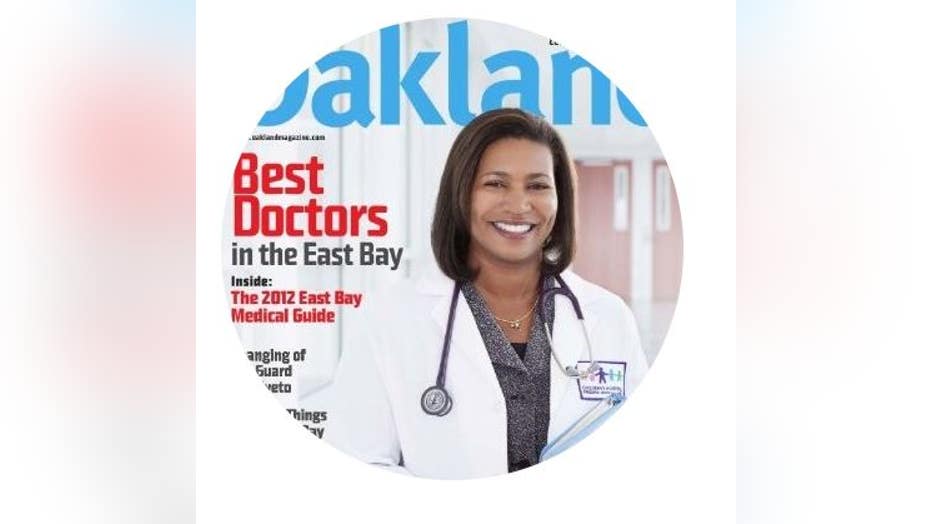

"This was not good for Oakland," said Dr. Pam Simms Mackey, who left her job as director of Graduate Medical Education and Pediatric Residency Program at UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital Oakland and is now the chair of Pediatrics and Chief of Graduate Medical Education at Alameda Health System. "They turned our big family upside down. They didn’t value us or our community. They were interested in penetrating the suburbs, like Marin and Walnut Creek and building up Mission Bay. Those in Oakland on public insurance were put in a long queue. Our patients weren’t catered to. Morally, that led to me leaving. Their narrative is that they’re saving us, but that’s not right. Yes, this is systemic racism."

The continued criticism comes as the nation is still grappling with addressing racial inequities across nearly every industry in the wake of racial reckoning stemming from George Floyd’s death.

FILE ART - UCSF Benioff Children's Hospital.

Services reduced, transportation difficult

Three examples of the complaints: Some departments that serve predominantly Black patients have been reduced and buying new equipment, such as an MRI machine, for an aging hospital hasn’t been a priority, they say. In addition, they say many services have been moved from Oakland to the UCSF Mission Bay campus, which is not on a public transportation line and costs patients money in bridge tolls and parking, making access to equal healthcare more challenging, if not impossible.

For instance, a social worker told a story of one mother who didn’t have a car had to take a free medical van from Oakland to San Francisco for her son to be seen across the Bay. The doctors took so long that she ended up leaving before the appointment was officially over. And so, she ended up skipping her son’s lab work because she felt she had to grab the van ride home to pick up her three other children at their Oakland schools.

"We have families who are having to travel to San Francisco and they don’t have the means to do so," said Domonique Trotter, an office associate at Children’s Hospital in Oakland.

The National Union of Healthcare Workers say that the East Bay has five times the number of children under 18 than San Francisco has.

But public records compiled by these workers indicate that surgeries in Oakland dropped by 24% from 2014 to 2020, while San Francisco operations increased by 5% from roughly the same time period.

"The movement of services and resources isn't following patient needs. Instead, resources are moving according to UCSF's bottom line and that needs to change," Laura Nakamura, a cardiac sonographer and candidate for Concord city council.

Medical staff have been writing letters and filing complaints for nearly a decade.

Doctors have met with U.S. Rep. Barbara Lee, state Senator Nancy Skinner, Oakland Mayor Libby Schaaf and various members of the Alameda County Board of Supervisors. Nurses also signed a petition to the UCSF Board of Regents -- the ones with the real power over this affiliation -- telling them that the economic impact of the merger has been "devastating" and that care must be improved for "all children regardless of race, color and socioeconomic status."

To date, nothing substantive has been done about their pleas and complaints.

This month, a group of healthcare workers held a public meeting where panelists, community members and politicians voiced their repeated concerns.

"UCSF has a responsibility to be accountable to the East Bay community," Oakland councilman Dan Kalb said.

State Assemblywoman Mia Bonta, who shared her own story of taking her children to the hospital when they were in respiratory crisis, added: "It is quite frankly heartbreaking. It is not what we expected of the merger. And quite frankly, it makes me mad."

UCSF Mission Bay campus.

UCSF says allegations are "false and misleading"

UCSF denies all the allegations that pertain to lesser care and providing unequal access.

No one from the hospital administration, including President Matthew Cook, would go on camera to answer inquiries from KTVU. However, UCSF's public relations team did address questions about the institution’s commitment to diversity and funding in a series of several emails.

Overall, UCSF administration insists that the "quality [of care] is increasing and access has expanded, especially for economically vulnerable patients." The PR department also refers critics to a website titled, "Setting the Record Straight," which touts a long list of UCSF expenditures and achievements.

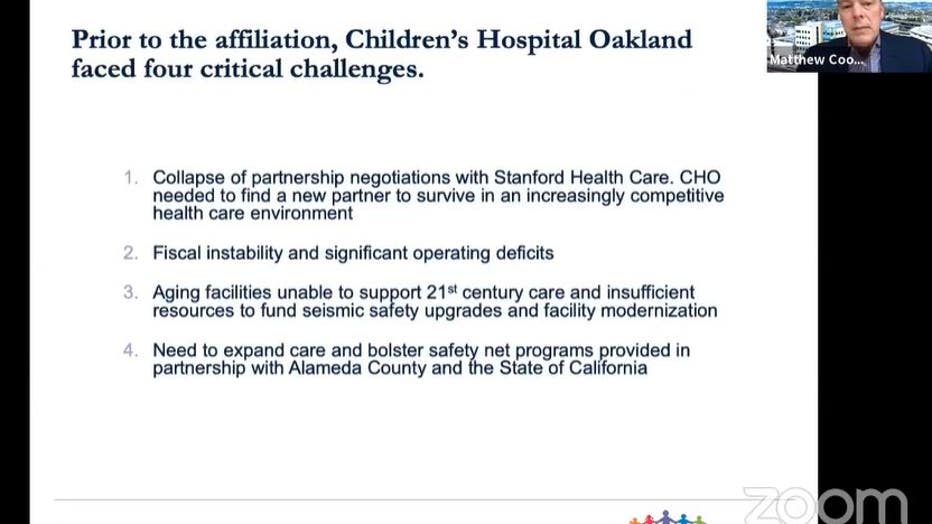

And in a March 2020 town hall recorded on Facebook, Cook extolled what he called "transformative changes" in pediatric health because of the affiliation. And he lauded Children’s Hospital Oakland’s "world-class" clinical care and integrated research between the two campuses.

"We’ve made significant progress," Cook said at the time. "We’re strengthening the programs."

Among the programs, the affiliation enabled Oakland's Pediatric Trauma Center to remain open, serving patients in the East Bay and beyond, "at a time when dozens of California hospitals have closed their emergency departments," the administration said in an email.

UCSF said its direct contributions have resulted in more than $181 million for Oakland’s pediatric MediCal patients, expanded Oakland’s specialty programs such as physical rehab, added new programs in sports medicine, Rheumatology and gender identity and overall allowed Children’s Hospital to "survive financially during the COVID pandemic."

Bottom line from UCSF: The affiliation has actually expanded options because patients can now receive care at either UCSF’s Mission Bay hospital or Oakland Children’s Hospital.

President Matthew Cook extolled what he called "transformative changes" in pediatric health because of the affiliation.

The public relations team also pointed to a $17-million National Institute of Health and California Institute for Regenerative Medicine grants announced this month that will fund a sickle cell research trial involving up to nine patients in Oakland and Los Angeles.

UCSF also pointed to a $1 billion expansion planned for the Oakland hospital campus, which will take an estimated 10 years to complete. According to a review of city records, this item has not yet been placed on the City Council agenda at this point.

And UCSF took aim with critics who claim that East Bay patients are sent to San Francisco to their detriment.

"This is an instance in which your sources are creating a misleading picture by cherry-picking information," the public relations team wrote. "[Decisions where to send patients] are based on where our pediatric patients can best receive the care they need."

Whistleblower files three complaints

But according to a whistleblower, it’s UCSF that is cherry-picking the information.

This whistleblower -- a doctor in a top management position who feels his job would be in jeopardy if he spoke publicly -- has filed three complaints with the California state auditor’s office since the merger. The most recent was in September.

Two of the whistleblower's allegations:

- CHO dropped from having six pulmonologists to two at a time when asthma and lung problems are more prevalent in poor, urban populations.

- CHO saw the "decimation of the landmark sickle cell program including loss of all pediatric physicians managing patients with sickle cell disease and all research staff leading to premature closure of vital clinical trials to treat this extremely vulnerable population." As an example, UCSF Mission Bay has 40 pediatric sickle cell patients while Oakland has 800 pediatric and adult sickle cell patients. (UCSF has since responded that they have since hired three sickle cell doctors to replace the ones that left in Oakland, but critics argue they are inexperienced. UCSF is also expanding some sickle cell research opportunities but veteran doctors say they are finding outside grant money and philanthropic dollars to rebuild the department that has suffered over the last seven years. They also argue that funding research is not the same as funding a full medical team to support patient care.)

"This is a Black Lives Matter issue," the whistleblower said. "I think that’s a perfect example where they talk about diversity and equity but what you see on the ground is the exact opposite. You see patients with less resources, often underrepresented minorities getting treated worse."

No one has tallied just how many veteran doctors have left in the last seven years, but anecdotally, the whistleblower and another high-ranking veteran doctor estimate that between two or three dozen doctors have left since the affiliation.

What that means: For instance, before the affiliation, it was easy to bump into a radiologist in Oakland to get a quick consult on a patient in the hallways of the hospital, at least three doctors told KTVU.

But now, many of the radiologists are gone, they said. Either they’ve quit or moved to San Francisco and so there is a lot of red tape and waiting around to get a radiologist’s report for doctors in Oakland.

It might take days or weeks now, compared to getting that information on the same day. Simms-Mackey, one of the doctors who left, told KTVU that it could even take several months to see certain types of specialists.

Doctors have quit in frustration

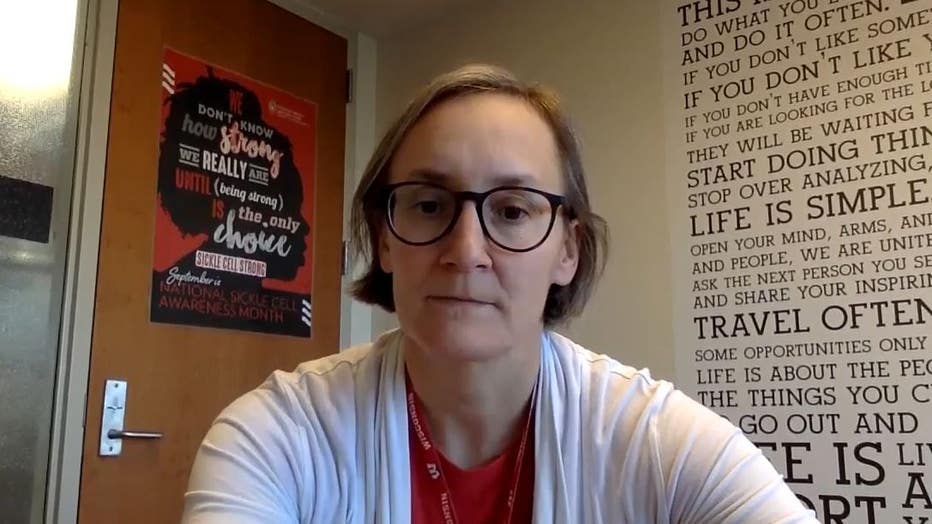

Dr. Anne Marsh was the medical director of Children’s Hospital Oakland sickle cell clinic from 2013 to 2020. But she quit in frustration and moved to work instead at the University of Wisconsin.

She was also My’Wayana’s doctor for years.

Marsh didn’t want to leave Children’s. She had thought it was the "perfect marriage of medicine and "social justice."

But she ended up resigning because she felt that UCSF paid a lot of lip service to diversity but didn’t financially back the "day-to-day aspects of actually caring for these patients."

Research grants are great, Marsh said, but that to really work, a sickle cell department needs experienced doctors, along with nurse case managers, social workers and special technology.

"You can’t just address the medical," Marsh said. "You have to provide whole person care."

She said she became "increasingly frustrated" that this holistic care wasn’t being funded or prioritized as it had been. Children’s Hospital Oakland had "always scraped by," she said. "But if you have a commitment toward equity, you have to fund some of these programs even though they will lose you money."

My'Wayna Stamps, 14, has been going to Children's Hospital Oakland since she was a baby.

Family is now contemplating finding care elsewhere

My’Wayna and her mother desperately miss Marsh and the care they received under her medical supervision.

Despite the numerical counterpoints that UCSF points out, there are subtle but important changes that can't formally be tallied in a spreadsheet. Namely: It's awful for patients with chronic diseases when their long-term doctors and support staff aren't there anymore.

Stamps and her daughter feel that UCSF might be focused on research, but not on a patient’s entire well-being.

"Being in a research lab and sitting face to face with a child are two different things," Stamps said. "I feel like they’re not that concerned about the mental state of these children that they’re taking care of."

Stamps is so upset that for the first time in her life, she’s thinking of finding care elsewhere for her daughter.

"Before the merger, I felt like I would never go outside anywhere of Children’s," Stamps said. "I’ve never thought about moving or leaving Oakland."

But now?

"Since the care that my daughter has been getting now, I have questions and I have looked outside of Children’s Hospital," Stamps said. "Why am I dedicating myself to a medical facility that doesn’t care about my child?"

HOW WE REPORTED THIS STORY:

Over the course of three months, KTVU heard from 30 doctors, patients, nurses and employees at Children's Hospital in Oakland, as well as politicians and community members in interviews as well as during public meetings.

Here is some of what they had to say:

Dr. Simms Mackey said the UCSF affiliation was "not good for Oakland."

State Assemblywoman Mia Bonta, (bottom row middle) shared her own story of taking her children to the hospital when they were in respiratory crisis, said: "It is quite frankly heartbreaking. It is not what we expected of the merger. And quite frankly

Dr. Anne Marsh, former head of the sickle cell pediatric department, said she didn’t want to leave Children’s Hospital in Oakland. She had thought it was the "perfect marriage of medicine and "social justice." But she ended up leaving because she fel

Dr. Lubna Hasanain trained at UCSF and is past president of Alameda-Contra Costa Medical Association. She said that there has never been an independent analysis of whether the UCSF affiliation has benefitted Oakland. "We need to have a third party lo

"We have families that are having to travel to San Francisco and they don’t have the means to do so," said Domonique Trotter, an office associate at Children’s Hospital in Oakland.

Hematology nurse Martha Kuhl said transportation issues and shuttered East Bay services have taken their toll. "It’s been very rough for many patients and families," Kuhl said.

Community Dr. Jaleh Naizi said that her patients can't afford to get to San Francisco and therefore, they often don't go.

Community Dr. Robin Winokur wrote an op-ed saying that the pact with UCSF was harmful to East Bay families. "UCSF promised an alliance that would create a bridge to top-notch care to all our kids, wherever they live. Instead, it’s become a patient fu

Ashley Momoh, 23, said that care changed when Children’s Hospital Oakland partnered with the University of California, San Francisco to become UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital Oakland nearly eight years ago. "Instead of the focus being on a curated h

Lisa Fernandez is a reporter at KTVU. Email Lisa at lisa.fernandez@fox.com or call her at 510-874-0139.