Privacy vs. community: Should schools require students to turn on cameras?

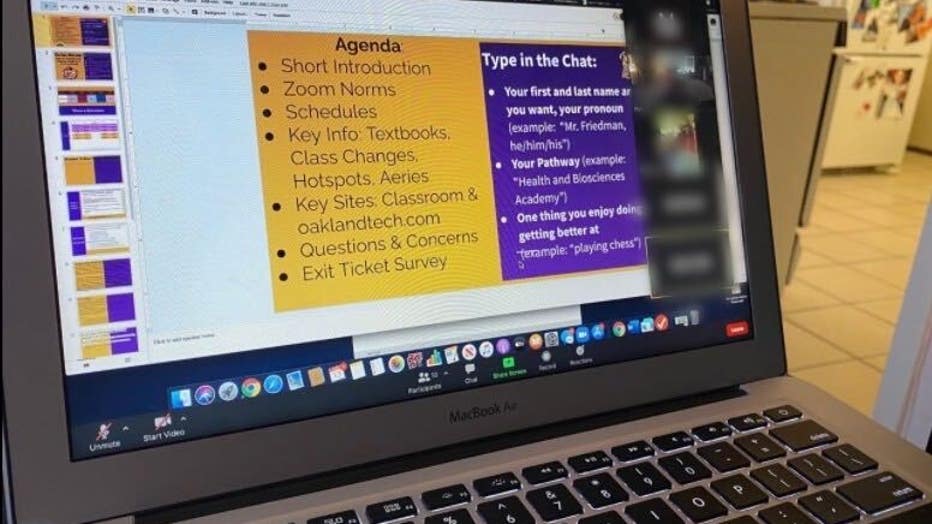

At Oakland High School, Isabel Park's 9th-grade English teacher came up with a creative compromise about whether to turn cameras on in class.

OAKLAND, Calif. - The rules at Liberty High School in Brentwood are clear. All students must turn on their cameras for class and keep them up the entire time.

"It's an attendance thing," said Landon Shaddle, 16, a sophomore. "If the screens are off, and we're muted and the teachers are looking at black screens, the kids could just get up and leave. They want to know we're there and learning. I'm fine with it."

While businesspeople forced to work at home because of the coronavirus outbreak have been arguing over the camera-on-camera-off issue since March, the debate is reaching new levels now that students are returning to classrooms online.

Privacy vs. community: Should schools require students to turn on cameras?

The rules at Liberty High School in Brentwood are clear. All students must turn on their cameras for class and keep them up the entire time.

The questions foster raging conversations on school listservs and over dinner tables. Should students be mandated to turn on their cameras and connect to the class to show eye contact and smiles? If their cameras are dark, how do the teachers even know they're there, or what they're up to? What about students who feel anxious with cameras on and people watching? And what if students live in a household with living conditions that they don't want shared with the rest of the class?

There are valid points on all sides.

One Oakland mother wrote this on a chat with other parents of high school students: "I think it should be mandatory for kids to be on camera. My son, for sure, needs more social interaction and even more importantly an expectation that to show up and be accountable and actively participate in class starts by turning the camera on. At the end of last year, his teachers demanded this and it made a tremendous difference."

But another mother responded that such a requirement would potentially harm some students. "Videos on does not necessarily lead to participation, engagement or connection," she wrote. "There are many ways of achieving this without potentially isolating or creating unsafe learning environments for our kids. We do not know what is going on for kids and families during this pandemic, please be patient with them and with each other."

There appears to be no consistency either on what the school camera rules are.

Some teachers and students want the cameras on in school and others don't.

While Landon, the student in Brentwood, must keep his camera on during class from 8:30 a.m. to 1:50 p.m., at an Oakland Unified high school, many students kept their screen dark during the first week of distance learning, which started Monday. District spokesman John Sasaki said students will not be mandated to keep their screen on, citing privacy reasons.

Still, one algebra teacher at Oakland Tech invited the students to turn on their video cameras and say hello, but he quickly said he understood if they didn't want to because of technological difficulties and privacy concerns.

That has left it up to teachers to establish their own standards.

Sara Shepich, a teacher at Global Family Elementary School in Oakland, said when she taught in the spring, she could see a student's father sleeping on the couch in the background with several other siblings in the room, too.

But because she teaches kindergarten, she said it's crucial that young students turn on their cameras, if they can, so she can see them and they can interact with their friends. If children are older, she said, it's understandable that they would want their cameras off.

Sara Shepich, a teacher at Global Family Elementary School in Oakland, Calif. said when she taught in the spring, she could see her student's father sleeping on the couch in the background with several other siblings in the room, too.

As coronavirus and distance-learning is a worldwide phenomenon, students, educators and parents across the globe are trying to balance privacy concerns with expectations for classroom performance.

Lexi Katsivalis, a 24-year-old high school teacher in South Africa, told KTVU via email that she's allowed students to make the choice themselves. And of course, she said, they have all chosen to keep their cameras off.

Her rationale? The school she teaches at caters to many students who do not come from wealthy or affluent households and "their houses might not be something they want to share with their wealthier peers."

Many of her students don't have high-speed internet and end up using their cell phones, which means turning on the camera zaps their data usage.

Lexi Katsivalis, a 24-year-old high school teacher in South Africa, told KTVU via email that she's allowed students to make the choice themselves. And of course, she said, they have all chosen to keep their cameras off.

The same disparities play out in city after city.

Dawn Finley, 48, a high school teacher in St. Louis, Missouri, told KTVU that remote learning is not something anyone signed up for and teachers have to remember that during remote learning they become "guests in our students' homes."

"Requiring a student to turn on their video stream can be traumatic and cause emotional harm," Finley added, saying that three students in one family could be sharing a kitchen table, some might be homeless and logging on from their car, while others have to go into their parents' work to sign into the class.

Then there's the issue of bullying: Finley said it is easy for students to take a snapshot of a Zoom screen and use it to harass and make fun of another student.

Turning on cameras, Finley said, should be a personal choice.

"Some students simply prefer to not be on camera and it is not our place to determine that for them," she said. "We shouldn't be looking at ways to take away their agency as human beings. No one should have to share their home space if they don't want to. It really is just that simple."

The issue of whether to turn cameras on or off in school is a matter of debate.

There is some give-and-take to be had.

Students could show their faces and turn on virtual backgrounds to hide their real surroundings if their computers allow them this function.

But at Oakland High School, Isabel Park's 9th-grade English teacher came up with a creative compromise.

She wanted her freshmen to meet each other and feel a sense of community, but she also wanted to respect their personal space.

So the teacher asked Isabel and her class to create a collage of photos that represent themselves, with pictures of her individually, her family and what's important to her.

That collage will be Isabel's profile picture in class, which will appear on her screen, instead of live video showing her every move.

"It's kind of nerve-wracking to have your camera on all the time," Isabel said. "It's really hard for some kids. At the same time, it would be really nice, especially if you're new to the school to see what your classmates look like."

Lisa Fernandez is a reporter for KTVU. Email Lisa at lisa.fernandez@foxtv.com or call her at (510) 874-0139. Or follow her on Twitter @ljfernandez.