Renowned Alameda artist dies in tragic sequence of events

Nancy Seamons Crookston painting a model at South Shore Centre in Alameda during a Plein Air event. Photo credit: Max Crookston

ALAMEDA, Calif. - Nancy Seamons Crookston, a designated Oil Painters of America Master and one of the most widely recognized artists in the nation, died Friday from complications while trying to save her painting arm. She was 74, a week away from her Thanksgiving Day birthday.

It all began in rural Hyde Park, Utah, where a little girl with perfect ringlets and a big bright smile discovered sidewalk chalk and decided she wanted to become an artist. With sheer determination and hard work, that girl would eventually become a prolific professional artist, represented in galleries and museums around the world, from Coronado to Charleston to China.

Seven decades later, as Crookston was walking with friends on her way home from breakfast in Alameda – her leather backpack filled to the brim with sketch books and pens – she tripped over a bump in the sidewalk, fell and broke her right shoulder: her painting arm.

Faced with one of the most difficult decisions of her life, she decided to have surgery to repair the bone for one reason, and one reason alone: to be able to paint again.

Initially, the surgery seemed successful; she was healing well. Little did she know a blood clot had developed postoperatively, and ended up in her lungs.

"I’m doing great," she told her daughter over the phone hours before she died. "You don’t need to worry about me at all. Seriously."

Crookston’s husband and true partner in life, Garr Crookston, was by her side every step of the way, even catching her when she collapsed the morning of her death.

They met in Cache Valley, Utah, when she was in her late teens and formed an instant, powerful bond that would keep them together for 56 years.

Fancy Nancy he called her.

Together they made a family with five kids and countless pets, and taught them how to love life and the important process of creating things, whether it was music or food or even a business.

Garr Crookston’s audiology practice and the family’s bread-and-butter, Hearing Zone, which grew to 11 offices across three states (Alameda, Oakland, and Albany, locally) was a true example of that. Everyone in the family pitched in and did their part to build the business and make it successful. Of course, his wife's paintings adorned the walls of every office.

"We were living the dream together," her husband said as he stood in the ER after her death with red eyes and tears running down his face. "And it all just ended."

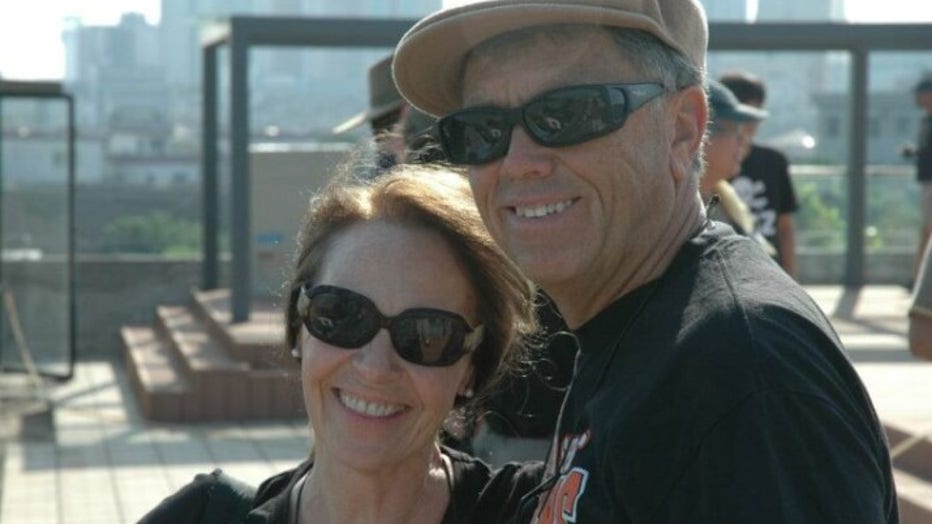

Nancy Seamons Crookston and her husband, Garr Crookston, at an art event in 2018. Photo credit: Oil Painters of America

Crookston juggled being a mom of five while being a full-time artist with complete grace and determination. She wore both hats so well people would frequently ask how she did it.

"She was such an inspiration to me," wrote fellow artist Sara Peterson, in an online tribute. "I saw some of her work in a gallery in Scottsdale over 20 years ago and I was just mesmerized by it. I became even more of a fan when I saw she had raised 5 children. It gave me hope and inspiration to keep painting when I started having kids."

Crookston’s kids all knew her haven was her art room, and even though you had to climb over mounds of art books and paintings to maneuver through it, it was a place of ultimate comfort and creativity, where you could join her at any time and talk about anything.

Nancy Seamons Crookston and family. Photo credit: Jesse Crookston

"One of my favorite memories of mom was getting home from school and running to her art room to see what she was painting," her middle son, Raymond Crookston, said. "I would watch her step back and think, then watch what she would add to the painting, over and over."

"But if we ever showed too much boredom while she painted," joked her oldest daughter, Amelia Bullock, "she’d tell us to go study the worms outside or find an interesting topic to explore."

Some things had to become less of a priority for Crookston, of course, like cleaning the fridge, which was always stocked with expired food because, to her, it was still chock-full of nutrients and too beautiful to throw out.

Crookston "loved a good rut" and hated that she had to take time away from painting for things like drying her hair or figuring out what to wear. She solved that problem by coming up with a uniform (jeans/black shirt/tennis shoes) she could simply throw on every day.

Nancy Seamons Crookston doing a live oil painting demonstration of a model in Charleston, South Carolina, April 2023. Photo credit: Oil Painters of America

But for special occasions, she knew how to take it up a notch and become the most gorgeous, vibrant person in the room.

One of Crookston’s favorite memories was the time she was trying to find the perfect outfit for an Oil Painters of America show she was judging in Santa Barbara. She felt she didn’t have the right clothes for the event, so she sat down at one of the busy shopping streets to people-watch, hoping to be inspired by one of the outfits of the women walking by.

"I saw the most classy lady walk by, so I stopped her and asked her where she got her clothes," Crookston recounted. "She looked at me crazy at first, but after an explanation and a stroll through Anthropologie together, she looked at me and said, ‘Let’s just switch clothes for the night and you can wear my exact outfit.’"

As fate would have it, they were almost exactly the same size, so they scurried into the dressing room to swap garb, giggling the entire time.

Crookston wore the outfit and said she received all sorts of compliments.

"You look so Santa Barbara," the owner of the art gallery said when Crookston arrived at the show.

The next morning, Crookston met up with the woman and swapped clothes again. They remained friends, and she sent the woman one of her paintings to thank her for her generosity.

Early on in her career, Nancy studied with renowned Russian artist, Sergei Bongart. She’d pack her bags for a few weeks every summer and head to Rexburg, Idaho, where she could be totally immersed in learning still life oil painting. Paint what you see, not what you know!

From penned sketches to watercolors to clay sculptures, she studied many art mediums and excelled in all of them. She was most widely known and awarded for her oil figure paintings, many featuring children on a beach, frolicking in the sand.

After raising the family in three states, including Iowa, Idaho and Utah, a sketching class at UC Berkeley in 2007 convinced Crookston that she needed to move to the Bay Area. How amazing the models were! It was like a candy store!

She found beauty everywhere and sometimes caught restaurant servers off guard when she would gush about their beautiful features and colors. It was almost like she was painting them in her head right then and there.

The servers and chefs at Ole’s in Alameda were some of her favorite subjects, and were very dear to her heart. In the end, she had sketched or painted almost everyone on the staff.

In fact, Ole’s staff was so saddened to hear of her death, they erected a memorial of her at the table that bears her name on a small gold plaque, the one she used to sit with her husband and sketch. They filled it with fresh flowers, photos of Crookston painting, and one of her sketches.

Ole's staff gathered around the memorial table for Crookston, November 23, 2023. Photo credit: Ken Monize

She felt music like her late trumpet-playing father and loved hearing his favorite big band music.

Christmas will never be the same for her kids without her cranking Harry Connick Jr.'s "When My Heart Finds Christmas." When that song was on, Crookston demanded her brood quiet down, as she stood tall, pounding her fist into the air for the chorus finale, tears swelling in her eyes.

And that wasn’t the only time Crookston took a stand.

Crookston became fierce when she heard about any injustice in the world. She fought for women's rights, and absolutely hated it if a man wasn't listening to a woman, or trying to talk over them. She would speak even louder, and forcefully, and demand they let her speak.

"I learned quickly to never speak over Nancy," her husband said. "Or she would let me have it."

Throughout her career, Crookston would go on to win numerous awards, including what would become her final, in October, the gold medal awarded at the Western Regional Exhibition for her painting, "I’ll Show You How It’s Done."

The painting features her great niece, climbing the metal gate of the family’s farm in a dress and cowboy boots and hat, looking confidently into the horizon.

Crookston's last award was the gold medal at the Western Regional Exhibition for her painting, "I’ll Show You How It’s Done," October 2023.

Learning until the day she died, Crookston was always determined to become better, taking class after class. The day before she died, she took an online gouache course, and unbeknownst to her, completed her final painting of Santa, a series she had started decades prior.

ALSO: 'Respect the ho ho ho': behind the scenes with Fairyland's Santa

In the final year of her life, Crookston -- always the artist -- was drawn back to the sidewalk chalk of her youth. She'd create whimsical creations of characters crawling out of the sidewalk for the neighbors to enjoy as they walked by.

"I feel heartsick, and will miss her," wrote Keri Bartlett Bullock in an online tribute. "Like thousands upon thousands of people, I felt so loved by Nancy. The world was her playground, and she has loved ones all over it."

Crookston will be honored with a California Art Club signature member designation posthumously.

One of Crookston’s wishes in life was for others to have the opportunity to pursue art without barriers. A memorial account under her name has been set up by her family for anyone wishing to donate and carry on her legacy: Nancy S. Crookston OPAM Memorial Contributions

Sara Sedillo is a digital reporter for KTVU and the daughter of Nancy Seamons Crookston.