San Francisco's famed Blackhawk jazz club showcased Black excellence

San Francisco's famed Blackhawk jazz club showcased Black excellence

Many people aren't even aware San Francisco's Blackhawk jazz club existed, but in its time, the Tenderloin dive bar regularly showcased Black musical excellence. It was where the city's native son, Johnny Mathis, was discovered.

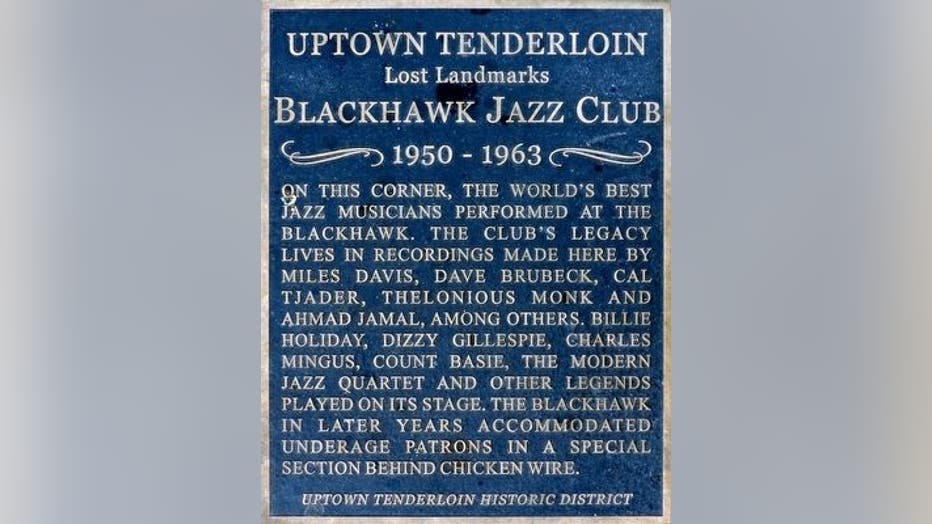

SAN FRANCISCO - Many people aren't even aware San Francisco's Blackhawk jazz club existed, but in its time, the Tenderloin dive bar regularly showcased Black musical excellence. It was where the city's native son, Johnny Mathis, was discovered. At the corner of Turk and Hyde streets, what is now a makeshift park in a neighborhood with a bad reputation, is where the likes of Miles Davis, Thelonious Monk, and Billie Holiday once graced the nightclub's tiny stage.

"It isn’t the music history that gets top billing in the San Francisco story, but maybe should. The Blackhawk enabled that world to break in a more widespread consciousness," Alex Spoto, program director of the Tenderloin Museum says reflecting on the club's historical significance. "The club launched the careers of Johnny Mathis, [Dave] Brubeck in a way, Gerry Mulligan, Cal Tjader all had extensive periods at the beginning of their career where the Blackhawk helped them build up their chops and get some exposure and in some cases, make some records."

The museum's exhibit on the Blackhawk includes a listening station that samples music recorded at the historic club. Albums famously recorded there by Davis and Monk are included.

The club's roster of players was dynamic and comprehensive for its time. Mongo Santamaria, Count Basie, and Lester Young are some of the other greats who performed there. The club was open from 1949 to 1963.

Among the live albums, Spoto says his favorite of the bunch is Ahmad Jamal's record. He said Basie famously crammed a big band onto its tiny stage.

Contemporary musicians recently paid tribute to the Blackhawk with an event at SFJAZZ Center.

Jeannine Anderson, a classically-trained soprano, was there for a soundcheck ahead of San Francisco Recovery Theatre's production called, ‘A Night at the Blackhawk.'

"My knowledge of the club is zero. My connection to the club is zero. Why is it important for me to be here tonight? To learn. To learn about the club," she says. "I've heard about it. I did some research before I came here tonight."

Geoffrey Grier is the executive director of the theater company.

"I’m still getting emails like, ‘Well, I mean, if the Blackhawk existed back then, how come we’ve never heard of it?’ Well, because it was torn down. Also, it was in a part of town people told you not to go into… Even back at that time, 1946, 1948, 1950, you know, the Tenderloin was poppin’, but jazz was like hip-hop. Back then it was like only the beatniks and only the people and the fringe society really got into jazz," Grier says.

He wrote ‘A Night at the Blackhawk,' a musical homage to the club. The production featured the musical styling of what it was like to be inside what was essentially a dive bar.

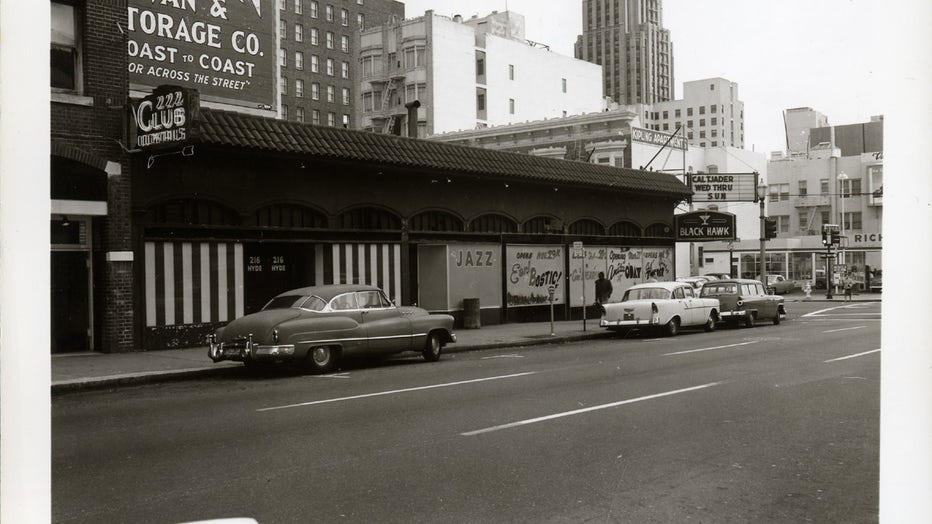

Exterior of the Black Hawk, January 27, 1961, the day after the raid for violation of liquor law. Photo Credit: San Francisco History Center/San Francisco Public Library.

"The Blackhawk was one of the first clubs to introduce Latin jazz to the West Coast," Grier says, referring in part to Tjader and Santamaria, neither of who is African American. "All the Latin jazz people came through the Blackhawk. It really piqued my interest, so I started to do some research, I kinda wrote this play." He explains his unique name, which references the bebop genre, for how he categorizes his musical. "I had this concept of this ‘bopera’. ‘I’m gonna do me a jazz opera. I'm gonna call it a ‘bopera’, and so that's how it developed."

Anderson doesn't try to fake it. She knows there is value in this under-the-radar story from San Francisco's past.

"I didn’t know that this was a venue for artists; Black artists, for people to be discovered….like you said, Johnny Mathis. So many others. I’m learning a part of my own history. A part of my San Franciscan history that I did not know," she says.

She explains the magnitude of the event at SFJAZZ and how the Blackhawk inspired an impressive collective of musicians and artists to come together this evening. "It’s important for me to be here, because first of all, to be surrounded by these amazing musicians and to just be a part of this community, a part of this music making. It’s my favorite thing to do. I think it’s important to have different voice types. We’ve got some jazz singers. We’ve got some blues singers, we’ve got some cabaret singers. And then you have little old me. The classical singer."

The collaborative spirit is part of the Blackhawk's legacy.

"I do know that there was a Sunday jam session that happened there for many years, regularly. And I think that jam session is where young Johnny Mathis would have been discovered," Spoto says. He says Helen Noga, wife of one of the club owners, left the club to manage Mathis full time.

Grier says an early incarnation of his production included a direct link to the Blackhawk in the form of saxophonist John Handy. The 90-year-old Oakland resident, a McClymonds High School graduate, actually played the club. The accomplished musician is considered "living jazz history." He went on to teach at San Francisco State University, UC Berkeley, San Francisco Conservatory of Music and Stanford.

Handy had suffered a stroke in recent years, but still recalls sitting in with Davis at the Blackhawk. "When Miles Davis played there, I sat in. I liked their music more than others," he says.

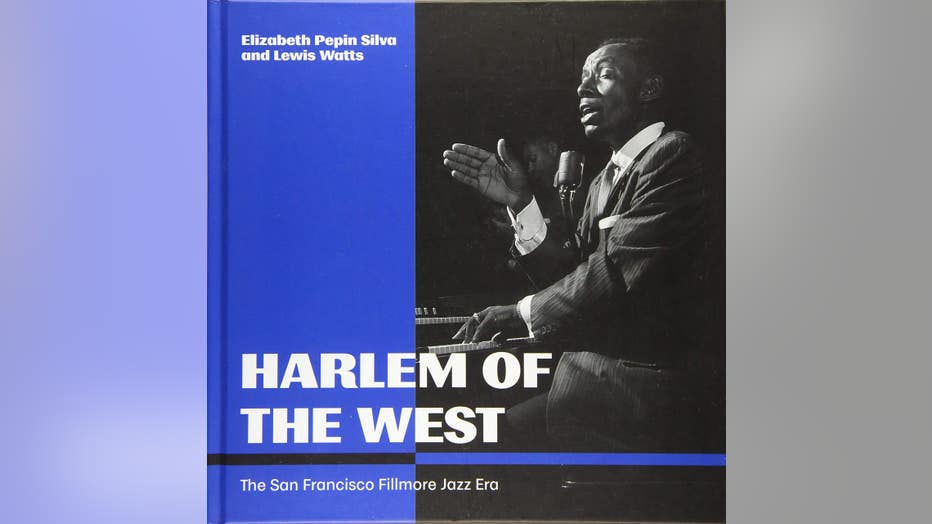

He moved around a lot from coast to coast, playing gigs on the Fillmore scene at a young age before entering the Army. Some of his oral history from that time is included in the superlative book, Harlem of the West.

You can't talk about San Francisco jazz without mentioning the Fillmore jazz era. Handy says he never used the phrase ‘Harlem of the West’ when he was coming up.

Spoto describes the vibrant music scene that existed along Fillmore and Post streets and how during the ‘40s and the ‘50s it became a predominantly African American neighborhood.

"Blacks from the South were coming out to work in the military operations here specifically." He mentions the great upheaval of the Japanese-Americans who had been living in that neighborhood prior, but were interned during WWII. "Harlem of the West was quite a vibrant scene, and was where a lot of the jazz clubs were. A lot of the live music was happening in both formal venues and informal venues because everybody lived around there."

While this scene was thriving, racism during this era was still pervasive.

"People forget how deeply and literally segregated San Francisco was before the civil rights era, and if you were a Black musician playing a gig east of Van Ness, you probably weren't walking in the front door of the club unless your name was on the marquee."

And east of Van Ness Avenue is exactly where the Blackhawk stood.

"And then you go and look it up and you see how the club looked and you realize that it was a neighborhood club. It literally was a hole in the wall, you know and all these guys would play at the Top of the Mark, they played at the Fairmont and all that kind of stuff, but when they got done, oh they were at the Blackhawk partying until 4 or 5 in the morning," says Grier. "It was the Studio 54 of San Francisco from way back when."

Spoto says the time period of the club's existence was transformative for the Tenderloin.

SEE ALSO: Songstress Carrie Cleveland still making music at 82

"Early 20th century, this neighborhood, while very working class, I think was quite robust economically. You had a lot of working people living in the SRO hotels. There were two world wars here, two world’s fairs. There was a very active port. There was blue-collar work," Spoto says. "And this was the area where a lot of those people would live."

He describes cabarets, diners, restaurants and bars that sprang up to cater to this demographic.

"It was one of the only clubs that permitted minors, restricted behind a chain," says Norman Brown, 86, of Oakland. He attended the club regularly. He worked as a photojournalist for the Sun Reporter, an African American newspaper based in San Francisco.

"You’ve gotta remember, they appealed to the youth. They did not exclude youth," says Grier. But while the club was considered inclusive for its time, a particularly conservative mayor was at odds with the Blackhawk and ordered raids.

Spoto talks about Mayor George Christopher. "He was preoccupied for a lot of his terms I think with cleaning up the Tenderloin. At one point in 1961 specifically, Mayor Christopher ordered a raid."

In fact, there are photos from the night of the raid that depict the caged ‘young adult’ area inside the club. It was where underage patrons could enjoy a Coke and jazz music, essentially from behind a chicken-wire fence.

Young adult cage inside the Black Hawk during San Francisco Police Department raid for violation of liquor law. This is the "caged" area for juveniles under the age of 21. Photo credit: San Francisco History Center/San Francisco Public Library.

Interior of The Black Hawk during San Francisco Police Department raid for violation of liquor law. Taken on January 26, 1961. Photo credit: San Francisco History Center/San Francisco Public Library.

"They typified San Francisco. They had like several raids. The police raided them. Everybody was trying to shut ‘em down and they said, ‘Oh. So the problem is kids are mixing with adults and there’s adult beverages? Ok, we’ll fix that,’" says Grier.

Of course, nothing lasts forever, not even the brilliance that was the Blackhawk. By Spoto's estimate, it was demolished in 1975 and became a parking lot.

The space is currently rented by Urban Alchemy, a nonprofit that employs people to clean up city streets.

Spoto describes it as a kind of public picnic space called the Urban Alchemy Oasis. Artist Adrian Arias' brilliant River to the Sky mural can be seen on the building next to where Blackhawk stood. It depicts Miles Davis and Billie Holiday; a clue to the locale's storied past.

Adrian Arias' River to the Sky mural in 2021. A mural depicting Miles Davis and Billie Holiday on the side of the 222 Club near Turk and Hyde where the Black Hawk jazz club once stood. The Luggage Store Gallery helped organize this mural funded by th

Music aficionados may know this historic landmark is an important part of the jazz tradition, but it represents so much more.

"This is something that examples what the Tenderloin really was and what the magnificence of this history really did produce and why it’s important for people to understand, be a part of and engage," Grier says.

Through music, the Blackhawk brought a mix of people together, both on stage and in the audience.

"Why I don’t know about it? Because where would you learn it if you’re not a musician, or if you’re not connected to a musician? I’m not a jazz musician. I’m connected to jazz musicians," Anderson says.

"But where else do you learn this? They certainly don’t teach it in school. You know? So I wouldn’t have a connection to it. It’s amazing that at my age, in my fourth decade, I’m still learning."

To expand your listening experience of music from the Blackhawk, check out KPOO DJ Harrison Chastang's curated playlist.

Young adult entrance at 216 Hyde Street for the Black Hawk, the day after the raid for violation of liquor law. Taken January 27, 1961. Photo credit: San Francisco History Center/San Francisco Public Library.

Corner of Turk and Hyde where the Black Hawk club once stood. (February 8, 2023)

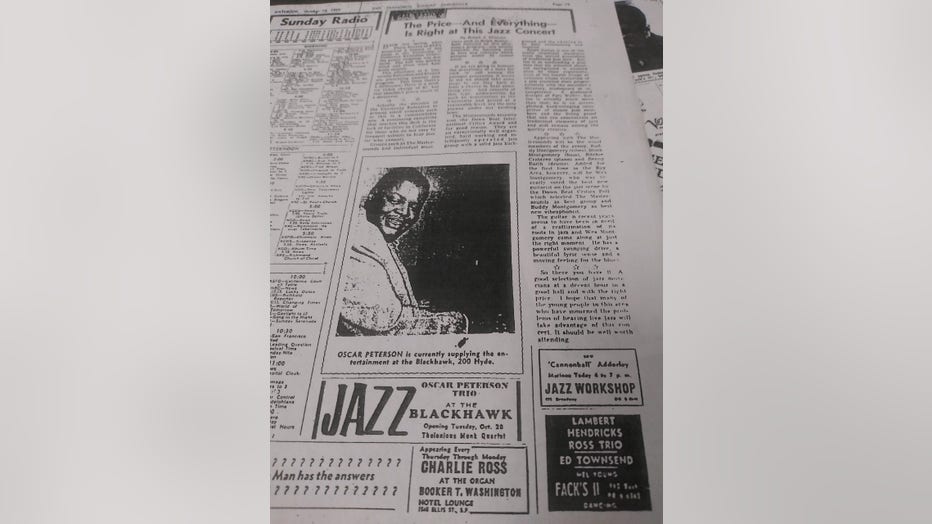

San Francisco Chronicle Datebook, Oct. 1959. Newspaper clipping shows an advertisement for 'Jazz at the Blackhawk,' featuring Oscar Peterson Trio and Thelonious Monk Quartet. Scheduled Oct. 20, 1959.

San Francisco Recovery Theatre's Geoffrey Grier at 'A Night at The Blackhawk' at SFJazz Center, Feb. 2 2022.

San Francisco Recovery Theatre's Geoffrey Grier at 'A Night at The Blackhawk' at SFJazz Center, Feb. 2 2022.