Schools are helping students who have lost loved ones to COVID-19

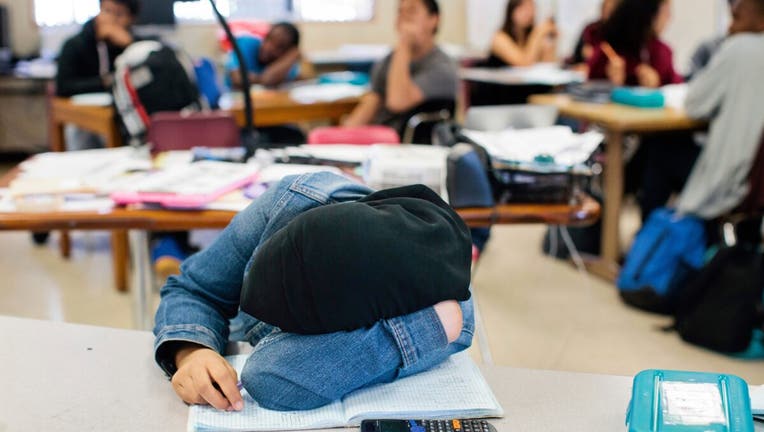

Freshmen attend Algebra 1 at Oakland Technical High School in Oakland, Calif., Monday, May 1, 2017. Photos by Alison Yin for EdSource

As campuses reopen, schools are bracing for an onslaught of student mental health needs. But they're also preparing to help students cope with something more elusive, more unpredictable and more profound: grief.

Thousands of children in California have lost parents, grandparents, aunts, uncles and other loved ones during the pandemic. More than 30% of students surveyed in March by the ACLU of Southern California said they'd lost someone close to them over the past year. Some had lost multiple family members.

COVID-19 has disproportionately affected Black, Latino and low-income communities, but almost every county in California has seen COVID deaths. Statewide, almost 65,000 people have died of the virus.

"I don't know any school that's been completely untouched by this," said Stephanie Murray, a psychologist at Whittier Union High School District in Los Angeles County and the mental wellness co-chair of the California Association of School Psychologists. "Every teacher I've spoken to has at least one student who's lost someone to COVID. And there's still more to come, unfortunately."

Grief affects everyone differently, regardless of their age, Murray said. Some experience the so-called five stages -- denial, anger, bargaining, depression, acceptance -- at different times, in a different order, and in varying intensity. Younger children may have a difficult time grasping that their loved one is gone permanently and lack the verbal skills to express their sadness. Adolescents might feel the loss acutely but hesitate to confide in adults.

Cultural and spiritual rituals and expectations also affect the grieving process, even for children. Some cultures set aside long periods for sadness, others expect grieving loved ones to return to "normal life" in just a few weeks.

In the classroom, students experiencing grief can express it in a variety of ways, said Josh Godinez, president of the California Association of School Counselors and a high school counselor in Corona-Norco Unified School District in Riverside County. Teachers should look out for students who are distracted, disengaged or withdrawn, or otherwise not behaving as they ordinarily would. He encourages teachers to discreetly take the student aside and ask open-ended questions about what might be bothering them, and refer them to a counselor if needed.

"Grief comes in all shapes and sizes, but for everyone, it means that life will forever be changed," Godinez said. "For students experiencing this, just noticing and caring can mean the world."

Listening is one of the most important things an adult can do to help a student who's lost a loved one, Murray said. Unlike other mental health conditions, such as anxiety or depression, grief isn't something that requires treatment, unless it becomes overwhelming and prolonged.

"What you want to say to a child who's grieving is, 'It's OK to feel sad. I'll sit beside you. You own this; this is yours,'" Murray said. "You don't want to negate or minimize their feelings. Really listen to what they have to say. Say, 'This is normal. What you're feeling is normal.'"

Social-emotional learning techniques, which many schools are already promoting as students return to campus, will also be helpful, she said. Yoga, mindfulness, wellness surveys, daily well-being check-ins and art projects should all be beneficial for students experiencing grief. Many schools have also hired more counselors and psychologists, and trained teachers to recognize signs that a student is struggling.

Jasmine Vo, a high school senior in Oakland Unified, lost her grandfather to COVID in 2020.

Jasmine Vo, a senior at Oakland High School in Oakland Unified, saw numerous close family members hospitalized with COVID last winter. Her grandfather, who likely contracted the disease at work, died of the disease in early January after a month in the intensive care unit.

Jasmine was devastated. Unable to focus on her schoolwork, she withdrew emotionally and fell behind academically. She felt her friends wouldn't understand. Her teachers gave her extensions on assignments, but it wasn't enough, she said.

"They moved the deadlines a week. But you can't get over a death in a week," Jasmine said. "Every time I tried to concentrate on school, I'd start thinking, should I be with my grandmother right now? My aunt and uncle are still in the hospital -- are they going to die, too? It was very hard. I literally broke down. I was not OK at all."

Eventually, Jasmine's parents intervened. They told her, "It's tough, but you still need to get your work done. Life goes on. You'll get over this," she said. Jasmine caught up with school, finished the year with straight A's and is applying to colleges.

"I think schools should give students time to get together and talk, offer more counseling," she said. "I was able to pull out of it, but it might be harder for other students."

For most young people, death is rarely an isolated event, Murray and others said. It might mean a family lost its primary breadwinner and now faces poverty or is forced to move. It could mean that family dynamics change, as each member experiences grief in their own way.

And for many children, a death from COVID could ignite fears that other family members will die of COVID, too.

"Kids want to know, will they lose someone else? Who's next? You want to reassure them, but the reality is, you can't," Murray said. "It's a real possibility that someone else might get COVID. That's what's so hard about this pandemic."

Aniyah Story, a high school senior in Oakland, struggled after losing her aunt during the pandemic.

Aniyah Story, a high school senior enrolled in independent study in Oakland Unified, lost her aunt to cancer in November. Although her aunt didn't die of COVID, the pandemic has greatly impacted Aniyah's grieving experience, she said. She couldn't see her aunt before she died; her family couldn't gather to mourn, and Aniyah felt isolated from her friends. Ordinarily, she'd reach out to a teacher, but she only knew her teachers virtually and didn't feel comfortable talking to them about personal matters.

"I was already depressed before. This just put a big strain on me," she said. "I had always been a solid student, but that semester was the worst I've ever done in school."

Eventually, she reached out to an adult at the wellness center where she was attending school at the time. She also began seeing a therapist outside of school and started painting and practicing yoga. Now she feels a greater level of acceptance of her aunt's death. She still misses her, but she's able to focus on school and college applications.

"I know a lot of people who lost family members last year," Aniyah said. "Schools need to focus less on academics right now and instead try to make school feel like a safe place. They need to focus on relationships. They need to make sure students know what resources are available to them. And they need to say it over and over and over."

For some students, grief will not be due to a death. Some students will have lost friends during the pandemic, or moved, or seen their family's financial stability decline, said Caroline Lopez-Perry, an associate professor of school counseling at Cal State Long Beach.

And some will have experienced all the above, plus the death of a loved one, she said. School might be the most stable thing in their lives.

"When someone dies, it creates an upheaval. That can be compounded by even more loss," Lopez-Perry said. "For students experiencing this, school can represent a return to normalcy."

Editors Note: This story was originally published by EdSource.