The dirty business of wetlands restoration

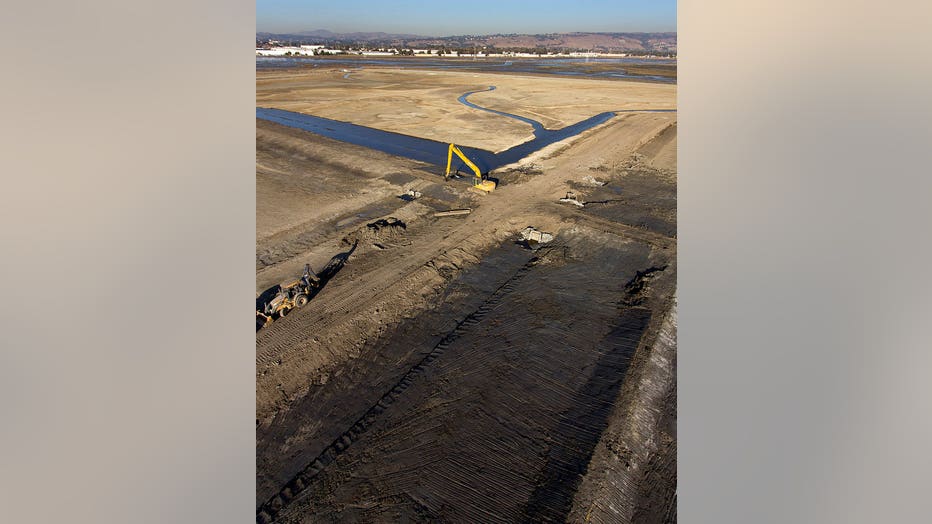

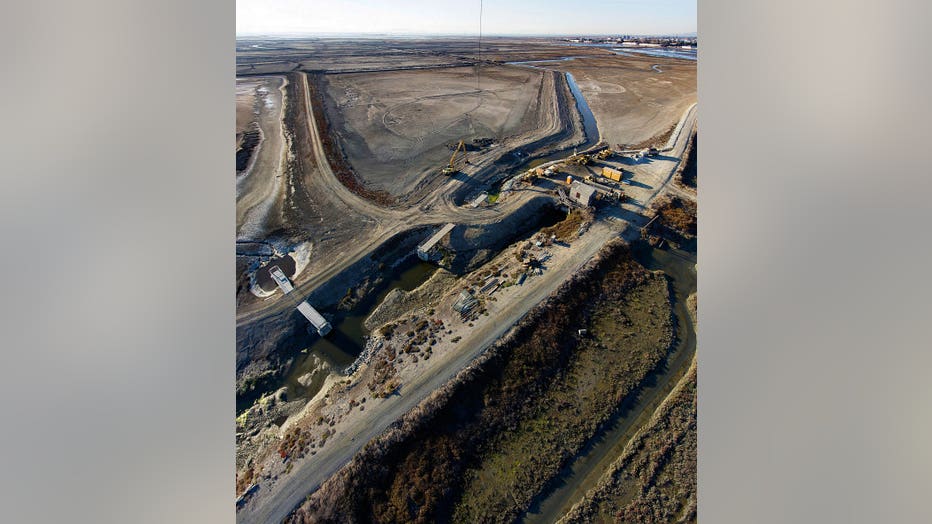

Four M Contracting, equipment operators, cut an area that will be a tidal marsh at the Contra Costa County Flood Control District's Lower Walnut Creek and Pacheco Marsh restoration project in Martinez, Calif. on Thursday, June 17, 2021. (Ray Saint Ge

On Oct. 29, the waters of the Suisun Bay breached the levee along the northern shoreline of Martinez and flowed into the Pacheco Marsh. The breach was the culmination of a process that took 18 years, $24 million in funds, and dirt. Lots of dirt.

"Dirt is cheap," said Paul Detjens, the project manager of the Pacheco Marsh restoration project, "but moving the dirt from one place to another is expensive."

Wetland restoration in the Bay Area requires massive amounts of dirt - or sediment - to protect against rising sea levels. Like the Pacheco Marsh, many of the Bay Area's coastal wetlands are degraded after decades of dredging, draining and construction activity. As sea levels rise, restoring them could be a long-term solution to build resilience against flooding, but acquiring enough sediment is proving to be an issue for some restoration teams.

Spectators and media members watch as the levee holding back Suisun Bay is breeched allowing water to flow into the 232-acre Pacheco Marsh in Martinez, Calif., on Friday, October 29, 2021. The flooding follows 7 months of heavy civil construction as

Tidal marshes like the Pacheco marsh are wetlands situated at the boundary between land and sea. When healthy, these ecosystems play an important environmental role. They act as carbon sinks and are natural habitat for a variety of wetland species, including the endangered salt marsh harvest mouse and Ridgeway's rail. Additionally, the vigorous vegetation the wetlands support acts as a natural barrier against seawater flooding. However, since the 19th century, wetlands across the Bay Area have been leveed, diked, and drained to accommodate urban expansion along the coast.

As a result, these degraded marshes have sunk below sea level, sometimes as much as 10 feet. Restoring these landscapes entails raising them to sea level or higher, and then allowing seawater to flow into them, by breaching levees or seawalls.

Save the Bay, an organization that works towards the preservation of the San Francisco Bay, estimates the region requires 100,000 acres of healthy wetlands to thrive. Of these, 78,000 acres of wetlands have been restored or are in the process of being restored all over the Bay Area.

The levee holding back Suisun Bay is breeched allowing water to flow into the 232-acre Pacheco Marsh in Martinez, Calif., on Friday, October 29, 2021. The flooding follows 7 months of heavy civil construction as part of the marsh and lower Walnut Cre

However, to raise thousands of acres of marshland to sea level, restoration projects need huge amounts of sediment.

Sediment is often largely composed of clay, but it must be tested to make sure that it is clean and that it won't cause any environmental damage once it is put in the marsh. In the case of the 232-acre Pacheco marsh restoration, Detjens said that his team lucked out.

"Our site was previously a disposal site for sediment dredged out of adjacent Walnut Creek in 1963 and 1973. So, unlike other marshes, we had plenty of extra dirt to work with." Thus, his team did not need to import any sediment from another location in the Bay Area, a process that he reckons would increase the total cost of the project by eight or nine times.

2008 and 2020 views of the levee separating Mt. Eden Creek Marsh and North Marsh at Eden Landing Ecological Reserve in Alameda County, Calif. (Photo courtesy Charles C. Benton)

In the absence of readily available sediment, restoration projects have two alternate sources of sediment: construction sites or the bay itself.

When material from construction sites is excavated, it must be tested and then transported to the site of the marsh. The San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission (BCDC) facilitates this process with Sedimatch, an online tool that connects construction projects with restoration projects. "It's like a dating app for sediment," said Detjens.

"Since we launched it a few years ago, there have been a few successful matches through the portal," said Brenda Goeden, who manages the sediment program at the BCDC. However, there is only so much construction activity taking place at a time and, hence, only so much sediment that can be acquired through this route.

Paul Detjens, Contra Costa County Senior Civil Engineer and Program Manager, at the Contra Costa County Flood Control District's Lower Walnut Creek and Pacheco Marsh restoration project in Martinez, Calif. on Thursday, June 17, 2021. (Ray Saint Germa

The alternative is to use sediment dredged up from the bay itself during the maintenance and widening of navigation channels near deep-water ports, harbors and marinas. While the bay contains a substantial amount of sediment, the process of extracting it from the water and transporting it to the restoration site is not easy or cheap due to the cost of dredging machinery, related power costs and specialized infrastructure required.

"If even dredging is not feasible, the last option for restoration projects is to allow the waters of the bay into the marsh and hope that the tides deposit enough sediment to keep the marsh level with the sea," said Goeden.

Such is the case with the Eden's Landing restoration project in Alameda County. Dave Halsing, executive project manager of the South Bay Salt Pond Restoration, said that while he would like to have used dredged sediment, the math just didn't work out. "The actual dredged sediment would not be expensive, but the infrastructure costs are immense," he said.

Construction at the site of Oliver Brothers Salt Works in Hayward, Calif., circa 2014. The site is part of the South Bay Salt Pond Restoration Project. (Photo courtesy Charles C. Benton)

Dredged sediment is typically deposited on a barge for transportation to a restoration project. But in the South Bay, the water is so shallow that barges can only come as far as the edge of the deep-water channels. So, to transport the sediment from a barge to the marsh site, restoration teams would need to install an offloader facility - essentially a massive bucket attached to a temporary wharf in the bay - from which sediment can be pumped to the restoration site via pipes.

Halsing estimates that the cost of the Eden's Landing restoration project is around $35 million, and that using dredged sediment would push that to a staggering $160 million. "Just running the power cables out to the bay to pump the sediments will cost $10-11 million, I kid you not," he said.

Instead, Halsing and his team are hoping that once they open the Eden's Landing salt marshes to the bay, the water itself will deposit enough sediment to sustain a thriving marsh. He is confident that if the project moves ahead in a timely fashion, a healthy marsh will be formed at Eden's Landing without any external sediment.

Work on a small-scale habitat improvement in Eden Landing Ecological Reserve in Alameda County, Calif. during the first phase of restoration in 2013. (Photo courtesy Charles C. Benton)

However, he points out that the critical test will come around 2050, when sea level rise is projected to accelerate dramatically in the Bay Area.

"Right now, marshes keep up with current sea level rise. But I do worry about the future, even though that is not in my control right now," he said. "What I hope is that, by then (2050) we will have an understanding of other ways of delivering sediments to the marshes, possibly through a public-private partnership model wherein costs of dredging are shared by government agencies, dredging companies and restoration projects."

A stitched panorama of work on a small-scale habitat improvement in Eden Landing Ecological Reserve in Alameda County, Calif. during the first phase of restoration in 2013. (Photo courtesy Charles C. Benton)

Editors Note: This story was first published on LocalNewsMatters.org.