Global outrage over IS group attack on ancient Iraqi site

BAGHDAD (AP) — Iraq's most revered Shiite cleric joined UNESCO Friday in decrying the Islamic State group's attack on the renowned archaeological site of Nimrud, a nearly-3,000 year-old city in present-day Iraq whose treasures were one of the 20th century's most significant discoveries.

The destruction is part of the Sunni extremist group's campaign to enforce its violent interpretation of Islamic law by purging ancient relics they say promote idolatry. Last week, the group released video of its fighters smashing artifacts in the Mosul museum, and many fear that Hatra, another ancient site near Mosul, could be next.

Iraq's Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani said in his Friday sermon that such destruction "demonstrates their barbarism and savageness and antagonism against the Iraqi people, not only in the present but also to its history and ancient civilizations."

In Paris, the head of the U.N.'s cultural agency called it a war crime.

Iraqi authorities were still trying to assess Friday exactly how much of the ancient site was destroyed when the militants bulldozed Nimrud on Thursday, since the area remains in militant hands.

"The destruction of Nimrud is a big loss to Iraq's history," Qais Mohammed Rasheed, the deputy tourism and antiquities minister, told The Associated Press on Friday. "The loss is irreplaceable."

A farmer from a nearby village told the AP Friday that militants began carrying tablets and artifacts away from the site two days before the attack, which began Thursday afternoon. The militants told the villagers that the artifacts are idols, which are forbidden by Islam, so it was necessary to destroy them, the farmer said, speaking anonymously for fear of reprisals.

UNESCO, however, has previously warned that the group was selling ancient artifacts on the black market for profit. Rasheed said authorities have not ruled out the possibility that the militants removed some of the artifacts to preserve them for sale before bulldozing the site.

In the 9th century B.C., Nimrud, also known as Kalhu, was the capital of Assyria, an ancient kingdom that swept over much of present-day Iraq and the Levant.

"It's really called the cradle of Western civilization, that's why this particular loss is so devastating," said Suzanne Bott, an archaeologist who helped stabilize structures and survey the ancient site for the U.S. State Department as part of a joint U.S. military and civilian unit.

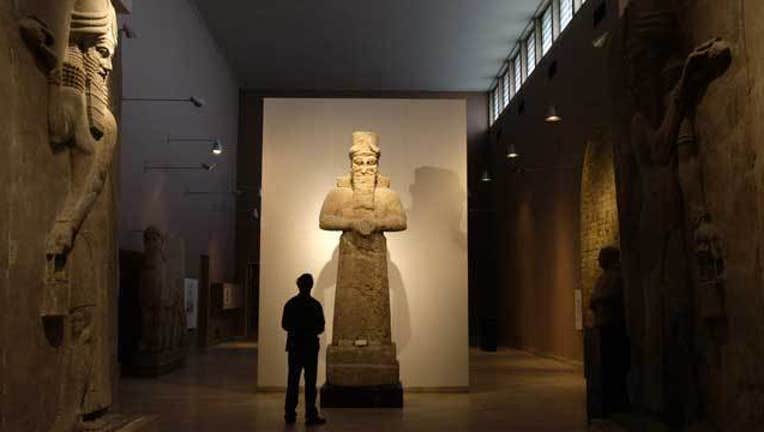

The site, which spans an area of 3.3 square kilometers on the Tigris River, boasted remains of temples, palaces and a ziggurat — or step pyramid — and was known for its monumental statues of winged bulls guarding the palace gates.

Many of the artifacts that hailed from Nimrud had previously been moved to museums in Mosul, Baghdad, London and Paris. The British Museum expressed concern Friday by reports that the site was bulldozed, saying "we naturally deplore all such acts of destruction of cultural heritage."

In the 1980s, archaeologists discovered a trove of hundreds of gold items from Nimrud's royal tombs — considered one of the 20th century's most significant archaeological finds. The "treasures of Nimrud" were kept in a basement safe of the Central Bank in Baghdad for years until they were "re-discovered" in 2003, and now most of it is in the Baghdad Museum.

Nimrud was already on the World Monument Fund's list of most endangered sites due to extreme decay and deterioration before it was captured by IS in June as the extremists took over nearby Mosul, Iraq's second-largest city.

"I'm shocked and speechless," said Zeid Abdullah, a Mosul resident who studied at the city's Fine Arts Institute until the extremists shut it down. "Only people with a criminal and barbaric mind can act this way and destroy an art masterpiece that is thousands of years old."

UNESCO Director General Irina Bokova denounced "this cultural chaos" and said she had alerted both U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon and the prosecutor of the International Criminal Court.

"The deliberate destruction of cultural heritage constitutes a war crime," she said. "I call on all political and religious leaders in the region to stand up and remind everyone that there is absolutely no political or religious justification for the destruction of humanity's cultural heritage."

Last year, the militants destroyed the mosque believed to be the burial place of the Prophet Younis, or Jonah, as well as the Mosque of the Prophet Jirjis — both revered ancient shrines in Mosul. They also threatened to destroy Mosul's 850-year old Crooked Minaret, but residents surrounded the structure, preventing the militants from approaching.

In July, they removed the crosses from Mosul's 1,800-year old Mar Behnam monastery and then stormed it, forcing the monks and priest to flee or face death.

A U.S.-led coalition has been striking the Islamic State group since August and preparations are currently underway to launch a large-scale operation to retake the city of Mosul. But U.S. and Iraqi officials have been cautious about setting a timeline for the operation as efforts to ready Iraq's embattled fighters continue.

Meanwhile the battle to wrest Tikrit — Saddam Hussein's hometown — from the Islamic State progressed Friday with Iraqi forces reaching the town of Dawr, 10 miles (15 kilometers) south of the city. Raed al-Jabouri, the governor of Salaheddin province, said Dawr is now under government control and he expects security forces to reach Tikrit by Sunday.

On Monday, Iraqi security forces launched a large-scale operation in an effort to retake the city from the militant group, but the extremists were able to stall the offensive somewhat by lining strategic roads into the city with explosives and land mines, military officials said.

Dawr is one of the first towns to be retaken in the Salaheddin offensive and is the hometown of Izzat Ibrahim al-Douri, Saddam's former deputy, who has been suspected of collaborating with the Islamic State militant group.