Friendlier prison guards? Why Gavin Newsom’s advisers want them at San Quentin

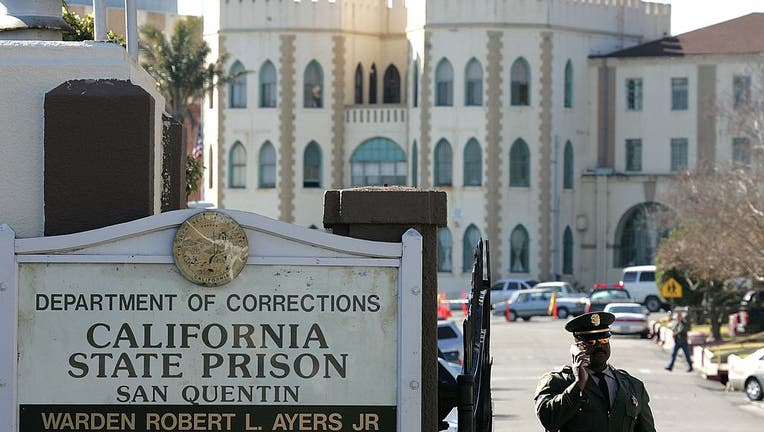

SAN QUENTIN, CA - JANUARY 22: A guard stands at the entrance to the California State Prison at San Quentin January 22, 2007 in San Quentin, California. The U.S. Supreme court threw out Californias sentencing law on Monday, a decision that could reduc

SACRAMENTO, Calif. - Converting a state prison into a rehabilitative center, as the Newsom administration seeks to do with San Quentin, means changing how guards do their jobs.

Instead of shying away from "overfamiliarity" with incarcerated people, prison guards should ask them about their families or favorite NFL teams. Instead of only reporting offenses, guards should note positive change in inmates. Instead of adopting a militarized footing against prisoners, guards should meet them in a common area to eat or watch movies.

Those are some of the recommendations from an advisory panel overseeing the conversion of San Quentin into what Gov. Gavin Newsom called a "model rehabilitation center."

A 156-page report released Jan. 5 by the San Quentin Transformation Advisory Council also calls for an end to double-person cells, and better housing for guards who stay on the prison campus in Marin County to avoid long commutes.

The report’s recommendations are not required to be adopted by the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation.

One of the biggest changes recommended would be retraining prison guards as "community correctional officers." In their new role, prison guards hired for this job would be retrained to understand the traumatic life experiences common to incarcerated people, substance abuse disorders, mental illness and anger management.

Guards with welding, plumbing or carpentry experience would be able to do vocational training in those subjects. Eventually, the community correctional officers would become part of an inmate’s rehabilitation team.

The report quoted an unnamed correction department official as saying: "We train staff like they are going to war. We’re not going to war. We have to change the training."

San Quentin houses about 3,300 of California’s more than 90,000 inmates. In March, Newsom pledged to transform the prison into a rehabilitation hub. He has marked four other state prisons for closure since he took office in 2019, a trend enabled by California’s falling population of state prison inmates.

Newsom looks to Norway on prison policy

The plan for San Quentin is modeled on prisons in Scandinavian countries, including Norway, which significantly decreased its rate of prisoners being convicted of crimes after release from 60%-70% in the 1980s to about 20% today when it began to allow prisoners more freedom and focused its prisons on rehabilitation.

In those prisons, incarcerated people can wear their own clothes, cook their own food and have relative freedom of movement within the prison walls. That model has taken root in states as disparate as deep-blue Connecticut and deep-red North Dakota.

California prison officials took a tour of Norwegian facilities in 2019 and said they came away impressed. The group included leaders from the union that represents state prison guards, the California Correctional Peace Officers Association.

Newsom estimated it would cost $380 million to remodel the prison as a rehabilitation campus. The new report from his advisory committee urges the administration to look for ways to reduce that expense.

Though California lawmakers have mentioned the prison programs in Norway and North Dakota as successful systems to replicate, it’s unclear exactly what California’s model will look like. That’s something the Legislative Analyst’s Office pointed out in a report last year, shortly after Newsom announced the conversion plan for San Quentin.

"While the administration has articulated some broad approaches to pursuing the goals of the California Model, such as ‘becoming a trauma informed organization,’ it has not identified any clear changes to policy, practice, or prison environments it deems necessary to achieve the goals," the report’s author, Caitlin O’Neil, wrote in May.

San Quentin already home to rehab programs

San Quentin, California’s oldest prison, has a lengthy list of maintenance needs that totaled more than $1.6 billion in 2021. But it also has an award-winning prison newspaper, the inmate-hosted podcast Ear Hustle and a program in which inmates can earn an associate’s degree in general studies after completing 20 classes.

Keith Brown, who served time at California State Prison, Corcoran and is still incarcerated at San Quentin, told CalMatters in July that the experience in San Quentin was notably better.

Corcoran "didn’t have any programs, really, and it (got) real hot there," Brown said. "Here it’s a little bit better. Asked the principal to take (a) class, and he got me right in."

The advisory report notes that San Quentin is a desirable location for inmates, with a waiting list that sometimes stretches for years, so the prison should take as many inmates as it can. But San Quentin also has major renovation needs, and the cost just to bring it up to code is prohibitive. The only way to do that, according to the report, is to reduce the number of inmates at San Quentin.

The complications go further still — California elected officials have shown a distaste for more prison spending while the prison population drops and would prefer to spend that money on community-oriented solutions, but cutting money to the prisons means fewer programs and worse living conditions.

"There is no magic wand that can resolve all of these tensions," the advisory group wrote in the report. "Policymakers will be grappling with these tradeoffs."

CalMatters investigative reporter Byrhonda Lyons contributed to this story.