Stimulus, unemployment checks help child support debt collection hit new high in California

Gabriel Lopez stands for a portrait at his work at Homeboy Industries in Boyle Heights on April 19, 2021. Photo by Shae Hammond for CalMatters

SACRAMENTO, Calif. - If Billy McCasland had gotten his $1,200 stimulus check, he would have moved his family out of the Modesto house the pediatrician says is responsible for his 7-year-old's lead poisoning.

L.A.-based single father Gabriel Lopez said he had hoped to take his youngest to the Selena museum in Texas, a bright spot after a tough year full of remote school and family turmoil.

And in Sacramento, Stacy Estes would have bought a car so he could get to work on his own, without scheduling shifts around his fiancee's workday. Any car would work, so long as it fit his budget.

But these fathers, all of whom owe thousands -- in some cases, tens of thousands -- in old child support debt didn't get the first federal stimulus checks. Instead, California clawed away money meant to be a lifeline for food and shelter during the worst public health crisis in a century, checks taken to repay decades-old debt.

The same thing happened when Estes applied for unemployment. His weekly checks went from about $80 to just over $60, not nearly enough to cover food, rent and utilities.

Across the state, many of California's low-income parents behind on government-collected child support payments saw their $1,200 checks that went out in the spring of 2020, along with enhanced unemployment benefits, intercepted last year. California responded with a good-faith effort to halt garnishments on the second and third round of stimulus checks. Department of Child Support Services Director David Kilgore said the state prioritized families by passing stimulus funds to custodial parents.

Still, records reviewed by CalMatters and The Salinas Californian showed the state kept a record $430 million last year, a 16% increase from the prior year, essentially taking from one government pot to pay back another.

Billy McCasland photographed at his parents’ home in Modesto on April 29, 2021. Photo by Anne Wernikoff, CalMatters

Parents saddled with child support debt told CalMatters they never saw their stimulus checks and federally funded $600 unemployment checks -- and the money didn't always go to their kids, either.

History of child support debt collections

Based on the idea that people who tap public assistance have a responsibility to repay the government, California intercepts child support payments from custodial parents who sign up for government aid such as CalWORKS. It imposes penalties like interest and driver's license suspensions when the noncustodial parents fall behind.

As a result, California charges noncustodial parents millions of dollars in interest on past-due child support payments, making it nearly impossible for many to land employment, support their children and pay off the debt.

California typically collects about $2.5 billion from parents each year through the Department of Child Support Services. Most of that money goes to custodial parents, but the state agency holds some of that back. In 2019, it kept about $370 million, half of which went to the state's general fund.

Those numbers -- from collections to retentions -- skyrocketed in 2020, which state data suggests is thanks to the state taking funds Congress approved to catch people teetering on the edge of an eviction cliff during the pandemic. Last year, the agency kept about $430 million of the $2.8 billion it collected, sending $207 million to the state's coffers, an increase of about 25% from the year before.

Stimulus checks and unemployment benefits accounted for so much of the money intercepted that it dropped the percentage typically collected through income withholding, where the agency takes money directly from noncustodial parents' paychecks. Job loss also contributed to the drop.

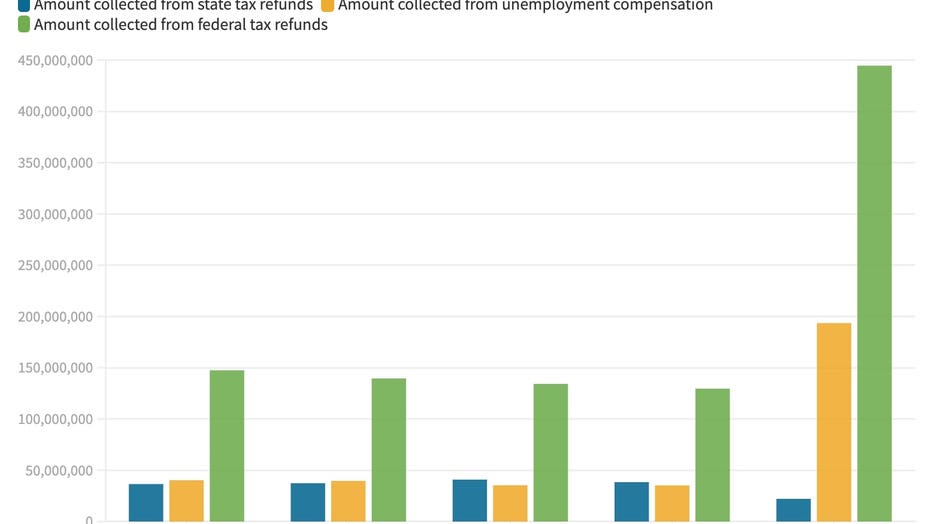

Source: California Department of Child Support Services (Table 4.4.1)

Normally income withholding accounts for 75% of the billions collected, but in 2020, the percentage dropped more than 20 percentage points.

Stimulus check interceptions fell under the category of federal tax refunds, which tripled from 2019 to 2020.

Interception of unemployment benefits leapt even higher after Congress authorized the base $600 payments authorized under the CARES Act. In 2019 the state agency intercepted $33 million in unemployment benefits. In 2020, that number shot up to $193 million. The state did not address interceptions for unemployment benefits.

That means stimulus checks and unemployment benefits from Estes and others were primarily responsible for the increase in child support collections during the pandemic.

Pay the parents first

While the most recent $1,400 and $600 checks cannot be intercepted by the state on behalf of the parent, in many cases the first check was intercepted to pay old debt owed to the state and federal government, Department of Child Support Services' Kilgore said.

Interception is typical for federal funds like tax returns. It is an easy way of getting additional money to pay down a parent's debt to the agency.

Knowing that the funds would be intercepted and the food and housing insecurity the pandemic had spurred, Kilgore said, the agency worked with Gov. Gavin Newsom to create an executive order that would funnel the intercepted stimulus checks to the custodial parent first, rather than the government.

Newsom produced an executive order in April 2020 to that effect, allowing "federal stimulus checks to flow directly to custodial parents owed back child support payments."

However, if none was owed to the family, the rest went to the government to repay old debt.

Golden State Stimulus checks cannot be intercepted. However, they can still be taken through a bank levy for delinquent child support payments, according to the Franchise Tax Board.

As a result, between 2019 and 2020, the amount of child support funds California kept for itself increased from $166 million to $207 million.

Lost chances

Stacy Estes drives DoorDash to keep up with child support debt owed to the state. Photo by Anne Wernikoff, CalMatters

Stacy Estes drives DoorDash to keep up with child support debt owed to the state. Photo by Anne Wernikoff, CalMatters

Advocates were outraged at the state's decision to keep any money for itself during the pandemic.The diversion of stimulus checks meant less money for families to pay rent or utilities, said Western Law Center Director of Policy Advocacy Mike Herald.

"There are millions of people in California who lost jobs at the start of the COVID crisis and it means those dollars went to pay child support arrears instead," he said.

Several fathers who owe tens of thousands in old child support debt shared letters they had received from the state instead of their $1,200 stimulus checks. The letters said the checks had been intercepted on behalf of the Department of Child Support Services.

To them, that lost money represented lost chances.

This article is part of the California Divide, a collaboration among newsrooms examining income inequality and economic survival in California.